Critical Comments

Comments and corrections to information on the website can be sent to green605@comcast.net.

In 2012 the first Pennsylvania historical marker commemorating Croghan was dedicated at the veteran’s memorial near Rostraver Township’s borough building, Westmoreland County.

Col. George Croghan (circa 1718-1782)

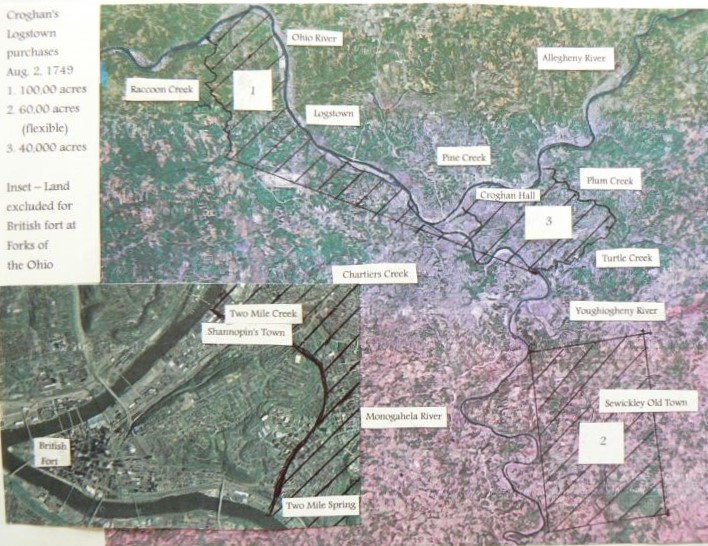

Veteran of King George’s, the French and Indian, and Revolutionary War, George Croghan’s 1749 grant includes most of Rostraver Township. Nearby Gratztown, named in 1780 for Croghan’s Jewish agents, was Croghan’s Sewickley Old Town trading post and anchored his local deed. Presumable purchasers were William Crawford for George Washington in today’s Perryopolis and modern Smithdale’s 1758 pioneer, George Weddell. Once a Monongahela Indian village, Weddell’s terrace farm overlooked the former Shawnee town and Croghan’s trading post, burnt by Wolf and other Delawares during Pontiac’s 1763 conspiracy, with partner Col. Clapham among the five killed.

An Irish immigrant and Pennsylvania fur trader in 1741, King George’s War found Croghan nearly engrossing Fort Detroit trade, fomenting an Indian revolt, and joining William Johnson on the Iroquois’ Onondaga Council. Croghan organized and led the Ohio Confederation at Logstown that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations and appointed Croghan its colonial agent. A few days before Celeron’s 1749 expedition reached Logstown, Croghan purchased his 200,000 acres from the Iroquois, later learning that the deeds would be void if in Pennsylvania.

He and Andrew Montour guided Virginia’s Ohio Company scout Christopher Gist in 1750 and arranged its 1752 Logstown treaty. Pennsylvania plans for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio had been abandoned in 1751 when Montour testified that the Indians did not want it. Virginia’s 1754 stockade was commanded by Croghan’s business partner William Trent and surrendered by half-brother Edward Ward.

A captain in charge of the Indians under Col. Washington, then under Gen. Braddock, Croghan could do little to capture Fort Duquesne, but William Johnson’s Deputy Indian Agent in 1758 hurried from facilitating the Easton Treaty to his Indian scouts at the head of Gen. Forbes’ column for its fall. He worked with Col. Bouquet and built the first Lawrenceville Croghan Hall, burnt during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Croghan brought Pontiac to Detroit in 1765 and, except for the Shawnees during Dunmore’s War, kept the Ohio tribes pacified thereafter.

Pittsburgh’s president judge, Committee of Safety Chairman, and person keeping the Ohio tribes neutral was exiled for treason in 1777 by General Edward Hand, who prevented Croghan’s return when cleared in a 1778 Philadelphia trial. The frontier lost its shield and the fourteenth state, with Pittsburgh its capital and Croghan the largest land owner, Indian agent, and likely governor.

Pennsylvania, Fort Pitt Museum, and the Daughters of the American Revolution declined Croghan’s historical marker for its most appropriate site, Point Park, and Pittsburgh’s Morton Brown responded, “the City does not prefer to simply deny your request outright.” When Westmoreland County ruled out Cedar Creek Park, Croghan’s pivotal story found public expression for the first time here.

Placed November 2012 by Greater Monessen Historical Society

and Rostraver Township Historical Society

Following are e-mail messages, most recent last, about the history on ohiocountry.us, particularly regarding George Croghan’s story beginning with the historian William Campbell, a professor at the California State University’s Chico campus who has written extensively about Croghan.

On Wed, Jun 23, 2010 at 12:52 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Mr. Campbell,

Can you help get a memorial for George Croghan erected in Pittsburgh’s Point State Park? Pennsylvania Department of Conservation Resources’s Frances Stein is the decision maker currently opposed to the offer from Greater Monessen Historical Society to place on a low stone base a one meter square granite slab with an etching of Croghan’s 1749 grants from the Indians totaling 200,000 acres, except for two square miles at the Point for a British fort and 200 words of his story to clarify what happened as a result? If not here, I think I tell the story coherently on the website ohiocountry.us. Croghan’s story puts Ohio’s history earlier than western Pennsylvania’s (written for Alfred Cave’s support), still it is reprehensible that Pittsburgh has not honored the man even by naming a street after him. Please call Frances at 724-953-6698.

Best wishes, Jim Greenwood P.S. Recently enjoyed reading your online New York piece about Croghan.

From: William Campbell

Sent: Wednesday, June 23, 2010 2:25 PM

To: Jim Greenwood

Subject: Re: Croghan memorial

Dear Jim,

I am not quite sure what you are asking me to do – the email was somewhat confusing. I’d be happy to help forward an attempt to have public recognition of Croghan. That being said, after a quick glance at your webpage, I do not agree with notable elements of your interpretations of the past. We both share an appreciation for Croghan and his contributions to early America, but I would need to know what exactly you are petitioning for – with reference to the wording – before I agree to make a call.

All the best, William

On Wed, Jun 23, 2010 at 2:59 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

William,

Thanks for your instant response. The 200 words have not been written yet, but would relate to the Point and its forts if the memorial is placed there. My work on Croghan is found at ohiocountry.us, including a critique of your 2009 article. We are in disagreement about Croghan’s public service, which was generous and unstinting, although undermined by his greed for land, particularly the 200,000 acres purchased in 1749. Opinions about his character are of secondary importance to historical accuracy, which has suffered by the obvious suppression of his story. To acknowledge it is deeply traumatic, for it is at odds with the national narrative that has a heroic George Washington as the central frontier figure. It is a myth and Croghan’s story is the reality that people like yourself have trouble accepting. People will have to get over it.

Jim Greenwood

From: William Campbell

Sent: Wednesday, June 23, 2010 5:06 PM

To: Jim Greenwood

Subject: Re: Croghan memorial

Dear Jim,

We are disagreement notably around the portrayal of a character, not the perpetuation of a nationalistic version of the past. I think you are very misleading when referencing a vaguely defined myth ‘people like myself’ have trouble accepting. My published work does not comment on such, and to reference me as doing so is inaccurate – not to mention somewhat humors considering my nationality.

As for as I can tell, you would like to see Croghan in ways like O’Toole sees Johnson. For myself, and other professionals in the field, this is very selective, “pop-history” – especially when one gets into notion of “Irishness” or nation building. Have you read Alan Taylor’s critique of O’Toole’s work in the New Republic? If not, I would suggest starting there. Moreover, having just spoken with Fintan last week about Croghan while in Toronto, I am not so sure he himself would disagree with the idea that self-interest was the prime mover behind Croghan’s actions. In this respect, I would argue, Croghan is not unlike his contemporaries. But, it is that story, the story of pragmatism and fluidity that I would argue plays a critical role in guiding the course of empire/nation in early America. It is a story unobstructed by ideological underpinnings historians tend to suggest motivated “great men” to do “great things.” So, if I understand your remarks correctly, the myth you imply I must “get over,” is the myth my work takes issue with.

With regard to Croghan, where we do agree is with regard to his importance in understanding the second half of eighteenth-century in North America. In fact, I would argue that Croghan had far more agency along the borderlands – and thus in the path of North America’s colonial past – than did the likes of Washington, Boone, or even Johnson. But that does not make him an incipient American, or a forgotten founding father, as Volwiler (and FJ Turner for that matter) saw him. By the early 1770s, those in Whitehall and colonial capitals that had an interest in the lands and people west of the Appalachians, hung on Croghan’s words and promises. As the evidence suggests, he was well aware of this, and made the most of it. And given his actions, I would suggest there is nothing “unstinting” about his public service. But for me, that’s what makes Croghan’s yarn so fascinating.

In the end, we both seek historical accuracy. How we approach obtaining such, is, perhaps, where we diverge. Regardless, I do enjoy talking about all-thing-Croghan, and hope our differences do not impede further discussion.

Do keep me updated with regard to plague – I would be happy to send a formal letter urging recognition of Croghan’s Indian deeds in the area. I must add, however, it may be of interest to you that the Haudenosaunee never received from Croghan (or his estate) the promised goods or sterling promised as payment for the lands in question!

with kind regards, WC

On Thu, Jun 24, 2010 at 11:23 AM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William,

Thanks for your nice reply. The myth of Washington as the central figure in late colonial frontier events is well defined, deeply ingrained, and international. What people have trouble accepting is Croghan’s story because it is at odds with a national narrative inherently false and perpetuated for centuries. I don’t think you have grasped his story yet and Fintan O’Toole is even more in the dark. It’s clear that you have yet to read my work on Croghan. When you do, I think you will find it clear, coherent, compelling and ground-breaking. Intellectually, most historians recognize that the nationalistic version of early American history is false but their emotional attachment to it overwhelms critical thinking, creating the sort of confusion I find in your opening remarks and which my first few sentences address

More than being just an American, Croghan was a Native American. Historians remain blind to this fundamental fact and focus on things like the debts and promises he defaulted on, rather than, for instance, that his descendants have been for generations the matriarchs of the Mohawks. His sense of responsibility for the safety of the frontier led him time and again to extraordinary acts of physical courage, even when old and sick. His recorded charitable acts are the tip of an iceberg that you have not properly gauged. No one in need was ever turned away from Croghan Hall and everyone relied on him for Indian guides and safe conduct when travelling farther west. As a western Pennsylvania, I am extremely proud of our finest and earliest great man, but that is irrelevant to our history, which has been suppressed and Croghan treated unjustly. Any comments you have on my work are appreciated. They have been met with a wall of silence at Heinz History Center and the region’s newspapers are not interested in my discoveries about the period.

Best wishes, Jim

From: William Campbell

Sent: Thursday, June 24, 2010 3:37 PM

To: Jim Greenwood

Subject: Re: Croghan memorial

Dear Jim,

Thanks for the email and continued dialogue. I think, however, a couple of points of clarification are needed.

First, and perhaps foremost, one would be hard pressed to locate the “well defined, deeply ingrained, and international” frontier myth you speak in most respected work on early America published in the last thirty years. In my field, one only has to point to the works Calloway, Taylor, Anderson, Richter, Barr, Havard, Greer….. the list goes on…… to illustrate just how different the profession is from your depiction. To suggest otherwise is to reveal the grasp out-dated histories of the frontier have on you. To this point, your statement that we, professional historians, exhibit an “emotional attachment to [the myth that] overwhelms [our] critical thinking” is blatant conjecture and without merit. I am not emotionally attached to those that I study, nor am I to a “national myth” with a supposed “international” reach. Canadian students of early North America, for instance, could care less about George Washington and his doings in western Pennsylvania. And on that note, did you not just mentioned that as “a western Pennsylvania” you are “extremely proud of [your] finest and earliest great man”?

I would argue that, when seeking out works that only relate to Croghan (as your reprisal suggests), you have limited the scope of your analysis. In other words, more reading is required. If you disagree, I would encourage you to submit your work to an academic journal for peer evaluation. “We,” that is professional historians, are not all on the same page, so perhaps another opinion might be in order. I’ll add here that thick skin is a requirement.

That being said, your commentary on the importance of Croghan to the tale that is the second-half of the eighteenth century in North America, is, to reiterate, where we find common ground. But, to state that he was “Native American” is, to be blunt, offensive. Moreover, to suggest that Croghan tirelessly engaged in acts of charity to protect the frontier and the people living there runs contrary to the mountain evidence that suggest otherwise – evidence that is not difficult to locate and document.

Have you read my PhD dissertation? Croghan is a central figure. And as mentioned in an earlier email, that story will soon be on my desk once I get this other book out of the way. When I do return to Croghan, I do hope we will have a chance to meet in person. We agree, the story of Croghan has been underrepresented, and I think we could learn much from each other given or shared interest in this colourful borderland character.

Best, WC

On Fri, Jun 25, 2010 at 9:51 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William,

If you read my work, there is absolutely no evidence of it in anything you have written below. Your comments are all in reaction to my e-mails. I am the first to publish Croghan’s Journal for 1763-64, an important contribution to scholarship that pales in comparison to the new things I say about him using sources you are quite familiar with, as you say. I am the first to say and provide evidence that he organized and led the Ohio Confederation that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the New York Iroquois; that he realized sometime in 1750 that if his 200,000 acre grant fell into Pennsylvania, it would not be recognized and knowingly began helping the Ohio Company by guiding Christopher Gist through Ohio; I am the first to claim that he had Andrew Montour lie to the Pennsylvania Assembly that the Indians did not want a fort at the forks of the Ohio. then quote the Half King calling Croghan an Indian and one of our council at the 1752 treaty with the Ohio Company. These are only a few of the new revelations about Croghan’s life that I uncovered. In place of anything specific about these remarkable discoveries, you have responded with the vague generalities and professorial arrogance found in your last response. Intellectual dishonesty and or emotional attachment to the narrative that Croghan’s story is at odds with fuels the denial of his story, signified by an attempt to shift the focus from what happened and why to his supposedly bad character. It is the traditional attitude toward him, yet you as a Croghan traditionalist accuse me of having “clearly pre-determined the end to the story.” What hypocrisy.

Best wishes, Jim

From: William Campbell

Sent: Saturday, June 26, 2010 11:44 AM

To: Jim Greenwood

Subject: Re: Croghan memorial

Dear Jim,

We have obviously hit a roadblock with regard to constructive debate. I hope we can remedy this.

I did read your work, in its entirety. You claim to be the first to do, say, and uncover many things with regard to Croghan, and that is simply incorrect with regard to most of what you just mentioned. That is why I suggested much more reading and research was required on your end. On that note, I’d be happy to send you specific information and references, especially as it relates to the specific points referenced in your last email. That being said, your stated position towards engaging further material is disheartening, and that is why I mentioned you seem to have a pre-determined ending to your story.

To this point, your continued insistence on assigning labels like “Croghan traditionalist” “denialist” and so forth, is inaccurate and very misleading. These sweeping statements suggest subtle and hidden agendas for those you are accusing. Speaking for myself, they are agendas that simply do not exist, despite your unfounded claims. That is why I suggested you appear to have more of an agenda, as a western Pennsylvanian and Croghan enthusiast, than I do. I am not seeking to tell the story of “great things” done by a State’s “first great man.” From a historical and cultural perspective, such an approach to the past is dated, very limited, and problematic.

In the end, we can only benefit from constructive criticism. That means, however, that you must be willing to reflect on the shortcomings of your work and be willing to do more research. I have read your work, despite your disbelief, and see a number of problems with your narrative and your claims of first authorship and “discoveries.” You, however, have not read many critical works related to this topic and area of study. To this point, I would be happy to send along references to help strengthen your analysis. But, as mentioned, much reading is required. This is not arrogance, Jim, it’s an offer and advice that you can chose to dismiss or utilize. It’s the process of writing history. My intension is not to come across as patronizing, but my problem with your approach to this topic is that you seem to have already dismissed resources and scholarly work that you haven’t even read.

I do hope we can salvage the discussion. Despite your dismissive comments earlier, I do think we can learn much from each other with regard to Croghan.

best, William

On Mon, Jun 28, 2010 at 4:45 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William,

Any thing specific you can say about my telling of Croghan’s story is appreciated, especially in regard to accuracy and originality. Forgive me for asking for the evidence that anything I have said is incorrect. Your take on Croghan is the traditional, generally accepted view of him as a scoundrel, something Wainwright tried very hard to substantiate and I think failed miserably, as I think you have. That’s a matter of opinion. I’m interested in facts about Croghan. You say most of the ones I’m discovered aren’t new or are incorrect and that much reading on my part is required on my part. That sounds to me like an evasion, but if there is anything new you or someone else has said of importance about Croghan, I’d be glad to read it. Please do send specific information and references . So far there haven’t been any. Having published my work on Croghan, the ball is no longer in my court.

Best wishes, Jim

From: William Campbell

Sent: Tuesday, June 29, 2010 11:43 AM

To: Jim Greenwood

Subject: Re: Croghan memorial

Dear Jim,

I will be sure to send along some specific references. But, give me a week or so to send you a list – I will also send you an electronic copy of my dissertation. I am in Chicago at the moment doing research, and my window isn’t that big, so I can’t afford to lose a day right now. But, I do have a couple of questions that will help expedite the process:

1) Have you already combed through the Wharton-Willing Papers, William Johnson Papers, Baynton, Wharton and Morgan Papers, and the Etting Collection at the HSP?

2) Have you read (off the top of my head), Stephen Auth’s “The Ten Years’ War”; Eric Hinderaker’s “Elusive Empires”; Jane Merritt’s “At the Crossroads”; Daniel Ward’s “Breaking the Backcountry”; Daniel Barr’s (ed.) “Boundaries Between Us”; Richard White’s “Middle Ground”; Alan Taylor’s “William Cooper’s Town” and “Divided Ground”; and Peter Silver’s “Our Savage Neighbor”? They are excellent works that will give you an idea about what the professional looks like as it relates to studies of interaction throughout the northeastern borderlands during the era of Croghan. You would benefit greatly from reading these works.

Oh, I almost forgot. There are problems with this article, but it is interesting. James Fennimore Cooper’s “William Cooper and Andrew Craig’s Purchase of Croghan’s Land” in The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association, New York History (12)4 1931.

Finally, I would like to ask that we both avoid making statements that are speculative and counter-productive. I am not, for instance, evading anything. Moreover, before stating someone’s work has “failed miserably,” perhaps you subject your own work to the rigors of professional criticism. There is no agenda in the historical profession to suppress well-documented arguments. A good argument based on solid research is always welcomed. To insinuate such, especially since you are not a professional historian, is again, quite frustrating. If you have run into some problems with regard to the acceptance of your arguments, you should check your facts, analysis, etc. Finally, the ball is always in your court, as it is mine, when there are points of contention.

Best,William

On Tue, Jun 29, 2010 at 12:53 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William,

Thank you for the reading list. Except for Cooper’s defense of his father’s

bargain basement purchase of Croghan property, I have not read the authors you cite or combed through anything. I assume you have and can point to something specific I have presented as history that is wrong. I don’t accept that Croghan was not an Indian, the evidence that he was is overwhelming. So was William Johnson and a number of other ethnically European and African people. I know I am the first to say and document that Croghan is the key figure for Ohio Country between the 1740s and the Revolution and the first to advance Wainwright’s work, the last important version of Croghan’s story. As far as I know, you are currently the leading professional Croghan scholar. The Croghan enthusiast on the Pennsylvania panel that found my text for a Croghan marker and brief history confusing is another professional historian, so is the woman who doesn’t think it would be a good idea to honor Croghan with a memorial at the Point so that people reading it could understand the region’s history. You have been combing through the records to dishonor Croghan, so you could write her with your list and a bibliography of the historians below who I guess you are saying support your position. What you can’t do is make a significant correction to my telling of Croghan’s story, or at least you haven’t yet. Which of my facts is wrong? Where does my analysis fail? If there is no agenda in the historical profession to suppress well-documented arguments, why is a non-professional the first to say that Croghan’s story is the key to understanding Ohio Country events? Without him at the center, only the superficial, disconnected, Washington-based current version is possible and the Ohio Indians permitting Virginia to settle and build a fort at the Point inexplicable. This becomes obvious to the average person reading my work, but for professional historians it is confusing, irrelevant, and in your case, without merit.

Best wishes, Jim Greenwood From: William Campbell Sent: Wednesday, June 30, 2010 6:24 PM To: Jim Greenwood Subject: Re: Croghan memorial Another follow-up… The first time Croghan’s 1763-4 journal was published was in December 1831 by American Monthly Journal of Geology – then reprinted in 1875 by the New Jersey Enterprise Book and Job Printing Establishment (Burlington, NJ, 1875).

On Mon, Jul 5, 2010 at 7:23 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote: Dear William, Have made the correction, thank you very much. Have read some of the books on your second reading list, and quoted historians you mentioned in early e-mails. I’m not doing much reading right now. I’m finishing the first draft of a novel, my first, or trying to. I also have a project going to compare the DNA of Monongahela and Omaha tribes to see if they are related. You’re busy with other things as well, so I appreciate the time and mental effort in offering corrections. You have an astounding interest in Croghan, for whatever reason, frankly it’s a mystery. Croghan was a heroic leader, so was Washington and that played out in a rivalry that had Washington replace Croghan as Ohio Country’s and Western Pennsylvania’s most influential person in 1777. Some of the horrible events that followed are mentioned on the map of Ohio Country on my website, so it might have been better if he had supported Croghan instead of suppressed him. The suppression of Croghan’s story is the story now and you have taken the part of finding evidence for Croghan the villain, instead of for what he did. Based on evidence mainly from his two biographers that make him the key figure in Ohio Country events between King George’s War and 1777, I am the first to say so and easily prove, as I believe my histories do, and factual corrections, like the one about the journal, are deeply appreciated. We Pennsylvanians have a tradition of treating everyone as friends, and I can see it is one of yours. Best wishes, Jim From: William Campbell Sent: Wednesday, July 7, 2010, 2:12 PM To: Jim Greenwood

Dear Jim,

I will be sure to pass along more specific references when I have time to review further – especially as related to the points you mentioned earlier, and those stated on your website. I am happy to hear I have been of some help.

I must add here that my intention is not to paint anyone a villain (again, I must correct you for making such statements) but rather to recount the events, personality, and thus the history of a person that is derived from extensive research. Research is what influences my portrayal of Croghan, and until you can find the time to analyze the slew of primary sources related to Croghan and early America, unfortunately your tale of “what he did” will remain incomplete. We both agree that there is much more to Croghan than what is offered in the pages of Volwiler and Wainwright – but getting to that story is a futile task if one doesn’t do the research.

All the best with your current work – it sounds very interesting.

Best,

William

On Wed, Jul 8, 2010 at 5:33 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William,

Thanks for the nice message. I will be happy to read anything you e-mail, including your dissertation. Any errors you find in my histories regarding Croghan or the Jumonville Glen incident would also be appreciated. Doubtless they are there, but I don’t think they will be material to the argument I make in the three booklets. Concerning Croghan, the format of a short biography does not lend itself to extensive detail or the complete story and I defer to Wainwright, Volwiler, yourself and other scholars in that regard. My understanding of Croghan’s life is still evolving, but I am confident that what I have written so far is accurate and a prerequisite for grasping the significant events in Ohio Country from the 1740s onward, and that it profoundly alters the accepted national narrative. The details of Croghan’s story are abundant. He was a prolific writer, as you well know, and relevant material can be found in profusion in libraries throughout the country. The research I have done informs my work and the research I have not done seems to me unlikely to contradict it in any significant way, but I will not be hard to convince if there is evidence that I am wrong.

Best wishes,

Jim

From: Alan Gutchess

Sent: Monday, July 27, 2010, 12:36 PM

To: Jim Greenwood

Mr. Greenwood, While we are not opposed to your marker, there is also nothing we can do to make it happen. The History Center’s management of the Fort Pitt Museum is for the museum only. We have no “site” outside of the actual footprint of the museum building, thus we cannot place a marker outside the building. Everything outside that footprint is DCNR, not PHMC or Heinz History Center. The decision making about markers in the park is, as I understand it, entirely the realm of DCNR and Riverlife. You must work through their system. We have no capability to bypass it for you. Alan Alan Gutchess Director Fort Pitt Museum Point State Park, 101 Commonwealth Place Pittsburgh PA 15222 412-281-9285 www.heinzhistorycenter.org From: Jim Greenwood [mailto:green605@comcast.net]

Sent: Sat 7/24/2010 3:11 PM

To: Alan Gutchess

Subject: George Croghan MemorialDear Dr. Gutchess, Greater Monessen Historical Society has asked the state to permit the placement of a memorial to George Croghan near the main entrance of Point State Park. It will be a meter square granite slab on a stone base with a 1749 map of Croghan’s land purchases excluding two square mile at the Point for a British fort and text about his role in regional events. Ohiocountry.us has the short Croghan biography and related work that informs the following: George Croghan (circa 1718-1782) [etching of his 1749 purchase and map of region] An Irish immigrant and Pennsylvania fur trader in 1741, during King George’s War Croghan engrossed Fort Detroit trade, fomented an Indian rebellion, and joined William Johnson on the Onondaga Council. He organized and led the Ohio Confederation at Logstown that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations, appointing Croghan colonial agent. Celeron’s 1749 expedition reached Logstown a few days after Croghan’s 200,000 acre purchase, void if in Pennsylvania. Late in 1750 Croghan guided Ohio Company scout Christopher Gist and arranged its Logstown treaty in 1752 after sabotaging Pennsylvania plans for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Ohio Company’s fort was commanded by Croghan’s business partner William Trent and surrendered by half-brother Edward Ward. A captain in charge of Indians under Col. Washington and Gen. Braddock, Croghan could do little to capture Fort Duquesne, but as William Johnson’s Deputy Indian Agent in 1758 he hurried from negotiating the Easton Treaties to his Indian scouts at the head of Gen. Forbes column for its fall. He worked with Col. Bouquet and built the first Croghan Hall, burnt during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Croghan brought Pontiac to Detroit in 1765 and kept the Ohio tribes pacified thereafter, except the Shawnees during Dunmore’s War. Pittsburgh’s president judge, Committee of Safety of Chairman, and the person keeping the Ohio tribes neutral was declared a traitor in 1777 by General Hand, who prevented Croghan’s return when cleared in a 1778 Philadelphia trial, dashing any hope for the fourteenth colony of Vandalia, with Pittsburgh as capitol and Croghan its Indian agent and largest land owner. Should the state refuse its offer, Greater Monessen Historical Society would like Heinz History Center to provide a site outdoors at Fort Pitt Museum. The Center’s mission statement should make approval almost automatic, for Croghan’s key role in regional history is undeniable. I will e-mail Andy Masich and others at the Center informing them of the offer and asking for their support, which I hope you will give as well. Best wishes, Jim Greenwood

From: William Campbell

Sent: Saturday, July 30, 2010, 12:17 PM

To: Jim Greenwood

Dear Jim,

My apologies for the delay. I have been on the move these few weeks and in-and-out of email contact.

I have looked quickly at the below text, and think it could use some factual/grammatical revision. The latter might be something is delaying the process. I would be happy to send you an edited version for review, but will need a couple of weeks to get to this. In the meantime, it might help your cause to contact the said individuals below that are considering placing this marker, and mention that you have contacted me and that I have agreed to help revise and edited the marker. Just a thought.

best, WilliamPS – what 1749 etching are you planning on using? There is more than one version.

On Mon, Jul 26, 2010 at 4:46 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:Dear William, Pennsylvania is dragging it s feet on placing the Croghan marker in Point Park. A message to Governor Rendell got some action and a response is promised in a few weeks. I’ve asked Heinz History Center to place the marker outside its Fort Pitt Museum and gave them the following description and text: The marker will be a meter square granite marker with a 1749 map of Croghan’s land purchases excluding two square mile at the Point for a British fort and text about his role in regional events. Ohiocountry.us has the short Croghan biography and related work that informs the following: George Croghan (circa 1718-1782) [etching of his 1749 purchase and map of region] An Irish immigrant and Pennsylvania fur trader in 1741, during King George’s War Croghan engrossed Fort Detroit trade, fomented an Indian rebellion, and joined William Johnson on the Onondaga Council. He organized and led the Ohio Confederation at Logstown that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations, appointing Croghan colonial agent. Celeron’s 1749 expedition reached Logstown a few days after Croghan’s 200,000 acre purchase, void if in Pennsylvania. Late in 1750 Croghan guided Ohio Company scout Christopher Gist and arranged its Logstown treaty in 1752 after sabotaging Pennsylvania plans for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Ohio Company’s fort was commanded by Croghan’s business partner William Trent and surrendered by half-brother Edward Ward. A captain in charge of Indians under Col. Washington and Gen. Braddock, Croghan could do little to capture Fort Duquesne, but as William Johnson’s Deputy Indian Agent in 1758 he hurried from negotiating the Easton Treaties to his Indian scouts at the head of Gen. Forbes column for its fall. He worked with Col. Bouquet and built the first Croghan Hall, burnt during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Croghan brought Pontiac to Detroit in 1765 and kept the Ohio tribes pacified thereafter, except the Shawnees during Dunmore’s War. Pittsburgh’s president judge, Committee of Safety of Chairman, and the person keeping the Ohio tribes neutral was declared a traitor in 1777 by General Hand, who prevented Croghan’s return when cleared in a 1778 Philadelphia trial, dashing any hope for the fourteenth colony of Vandalia, with Pittsburgh as capitol and Croghan its Indian agent and largest land owner. Best wishes, Jim Greenwood

August 4, 2010 letter

Dear Mr. Greenwood,

Governor Edward G. Rendell has asked me to respond to your letter that you addressed to him on July 12, 2010, regarding your request through the Greater Monessen Historical Society tio install a memorial at Point State Park in honor of George Croghan.

Please know that interpreting the park’s historical, cultural, and natural resources is important to the Bureau of State Parks, especially in this case at Point State Park in Pittsburgh. In the year 2003, the Point State Park Comprehensive Master Plan was developed to address various items necessary to the operation of the park. On of the findings of the master plan was the need for a specific interpretive plan. The Point State Park Interpretive Plan was completed in January 2009. This plans notes that the main interpretive theme of the park focuses on “The Point’s strategic location at the Forks of the Ohio [which] has rendered this a place of international consequence and importance.” The plan also addresses waysides, exhibits, publications, and programming with the Fort Pitt Block House and the Fort Pitt Museum. The 32 recommendations in the plan provide for a cohesive visitor experience. This includes recognizing the National Historical Landmark designation, recreational uses of the park, environmental concerns and the space limitations of the 36-acre park. Several of these interpretive recommendations are currently being developed.

Although George Croghan was an important figure in the history of the region, we can not approve the placement of a memorial in his honor on state park property. One concern noted during the development of the two plans I referred to above was the potential of having too many signs in the park. Much of the interpretation recommended in the plan calls for the use of various techniques to connect resources to the visitor (programs, publications, audio, website, etc. . .) rather than signs or memorials. As an alternative to a memorial for Mr. Croghan, you may wish to consider developing a program or brochure that would be available to the public to tell the story of Mr. Croghan.

Thank you for your interest in Pennsylvania State Parks. If you have any questions, please contact Lori Nygard, Park Operations and Mainenance Planning Division, at 717-783-3307.

Sincerely,

Signed David A. Sariano for

John W. Norbeck

Director

Bureau of State Parks

P.O. Box 8551

Harrisburg, PA 17105-8551August 9, 2010

Mr. John W. Norbeck,

Director

Bureau of State Parks

DCNR

P.O. Box 8551

Harrisburg, PA 17105

cc: Governor Edward G. Rendell

Dear Mr. Norbeck,

Thank you for a response to Greater Monessen Historical Society’s request to place a George Croghan memorial in Point State Park. In declining the offer, you list as one concern the potential for too many historical markers in the park. No other concerns are mentioned, but I have heard the La Salle plaque used as an example of inappropriate signage. A Croghan marker is not only appropriate, but essential to understanding the history of the Point and links the markers already there. There is only one history of the Point and from 1749 into the Revolution, the period of its international significance and importance, George Croghan is central to it, as the marker text and image of his 1749 land purchases makes clear.

Speaking for Greater Monessen Historical Society and as a regional historian, it is impossible to know that interpreting the park’s history is important to the Bureau of State Parks as you ask us to do, otherwise you would not deny visitors to the 36-acre park the vital historical information found on the Croghan marker and nowhere else in the park. An alternative site will be found for the marker this year and it will remain for centuries to come a reproach to the Bureau of State Parks and Pennsylvania during Governor Rendell’s administration.

Sincerely,

James R. Greenwoods

Dear Jim,

Thanks for the update. The start of a new semester is approaching and I am on deadline for my first book project. As a result, I will not be able to get back to all-things-Croghan for a couple of months. My apologies for the delay, but I must plow thorough the necessaries first. As for Washington being a scoundrel, you don’t have to convince me of that! When it came to western lands, most speculators were.

Have you read the book “The Indiana Company” by Lewis? If not, I would suggest getting a hold of it. It’s an oldie, but a goodie with regard to the evolution of speculation and land claims in the Ohio Country.

All the best,

William

On Sat, Aug 21, 2010 at 3:43 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote:

Dear William, Here is a photo of what will be etched on a sixteen by twelve inch piece of black granite and affixed to the Croghan marker: As you probably know, William Crawford wrote Washington about how that scoundrel Croghan was not satisfied when the survey for his 100,000 acre deed was run and had it run again from a starting point farther up the Monongahela River to deprive Washington of land that he claimed on Chartiers Creek. The implication was that Croghan was taking in more than the 100,000 acres that he purchased from the Indians, which may have been true, but the above image establishes the certainty that the first survey was around 40,000 acres short of 100,000. Coupled with Margaret Bothwell’s discovery that Washington’s deed for his land was dated three years into the future and signed by Governor Dunmore on July 5, 1775 when he was on a British Man of War on the York River and Washington had just taken command of the Continental Army at Boston, and that in 1784 Washington journeyed to court in Western Pennsylvania to have fifteen or more families evicted from property they bought from Croghan and had been living on for more than twenty years, perhaps you can understand some of why I admire Croghan and think Washington was a scoundrel. Best wishes, Jim

From: Jim Greenwood (by way of Noam Chomsky )

To: Noam Chomsky

Sent: Monday, August 23, 2010 11:22 AM

Subject: George Croghan’s storyDear Dr. Chomsky,

Our national narrative is at odds with the life of George Croghan, which explains seminal historical events regarding George Washington, details found in 1925 and 1959 Croghan biographies. My Reappraisal on website ohiocountry.us is a short update. Intellectually, few still believe the Cherry Tree Myth, yet the story it was created to counter remains taboo. Can you help break it?

Best wishes,

Jim GreenwoodFrom: Noam Chomsky

Sent: Monday, August 23, 2010 12:47 PM

To: Jim Greenwood (by way of Noam Chomsky )

Subject: Re: George Croghan’s storyThanks for letting me know about all of this. As for the Washington myths, I thought they were pretty well exploded by work like Larry Friedman’s some years ago.

NC

—– Original Message —– From: Jim Greenwood (by way of Noam Chomsky ) To: Noam Chomsky Sent: Monday, August 23, 2010 2:48 PM Subject: Re: George Croghan’s story

NC

Haven’t read Friedman, but believe my 2002 booklet on Jumonville Glen is the first to point out that Washington lied about how many men he had there. Only later did I realize that the Cherry Tree Myth grew out of this and the other misrepresentations he made about the incident. He would not have been there except that Croghan had purchased 200,000 acres from the Iroquois at Logstown a few days before Celeron arrived on his expedition claiming the upper Ohio Valley for France in 1749. About a year later Croghan realized that if his deeds fell into PA, they would be void. He had organized and led the Ohio Confederation that PA recognized as independent of the New York Six Nations after being put on the Onondaga council in 1746. In 1748 PA appointed him its colonial representative, in effect he negotiated with himself. It was no trick to buy the 200,000 acres or get the Ohio tribes to make a treaty with the hated Virginians of the Ohio Company, but it profoundly altered history. From King George’s War beginning in 1744 until 1777 when he was Pittsburgh’s president judge, Committee of Safety Chairman, and person keeping the Ohio tribes neutral so the British and their Indian allies could not raid the frontier, he was the key figure in the region’s events. His long rivalry with Washington, beginning with the Fort Necessity campaign, ended in 1777 when he was declared a traitor. He cleared himself in a 1778 Philadelphia trial but was not permitted to return to his home and fur trading business in Pittsburgh. Your sense of justice and disdain for the right-wing politics based on suppressed history may not shield you from the trauma Croghan’s story induces in people. Thanks for your interest,

JimFrom: Noam Chomsky

To: Jim Greenwood

Sent: Monday, August 23, 2010 3:31 PM

Subject: RE: George Croghan’s story’Sounds very interesting. Will try to find time to pursue these leads. NC

From: Brown, Morton Sent: Wednesday, August 25, 2010 4:17 PM To: green605@comcast.net Cc: Molnar, Katherine Subject: Croghan PieceMr. Greenwood,

I just called and left a message on your home phone, but though that I would give you some thoughts in an email incase we keep missing one another.

I have reviewed your description of the Croghan monument and think I understand from your last email that you are now seeking to place the piece in Schenley Park, and all of the other locations you mentioned are now off the table: Point State Park, Gateway median, Lawrenceville, etc.

I would offer the following questions and suggestions to you regarding this proposal:

1) Why this person/why this site? The first question/burden on your part is to clearly describe the relationship of the proposed monument/historical marker to its proposed site. You mentioned a family relationship between Mary Schenley and Mr. Croghan, but what is the direct connection between Croghan and Schenley Park—the proposed site? Is there a direct connection?

2) If there is already existing signage and interpretive information regarding Mr. Croghan in Point State Park (seemingly a more appropriate location in any case), then why would the City want or need to provide another plaque or space for a monument to this same person in another public space? Residents and visitors already travel to Point State Park with the intent of visiting an historic site and museum and are generally interested in history of this kind—this is a known historical location that already makes mention of Mr. Croghan. In your opinion, it seems, Mr. Croghan needs more attention than he is currently getting and the way to get this from your perspective, is to place another marker in a city park. You would need to develop a very convincing argument to this point if you proceed.

3) The proposed text for the piece needs work. You should get a professional to draft concise and appropriate text for a piece like this that matches in scale in scope other historical references or interpretive signage. The proposed text is a little hard to follow and could use some grammatical work as well.

4) The proposal description states that the piece itself would be made of granite approximately one meter square. What is the rationale behind this? You should consider whether this piece should be a memorial, monument, historical marker or historical plaque and be prepared to explain your reasoning as to what you have decided upon. Again the context of the site in relation to the piece is an essential consideration. It sounds to me that this project would be better served by taking on the manifestation of a historical marker (those blue metal signs with the yellow text) or an historical plaque that would be placed in a site that would have relevance and a direct connection to the referent—Mr. Croghan. Consider, for instance, Is there a spot in Pittsburgh where there was an overland passage for the fur trade that Croghan was a part of….?

At the end of the day, you could propose this to the City’s Art Commission and the HRC and the two Commissions along with City administrators/Parks and Public Works Directors’ approval could decide the matter.

We do not have a strict policy on monuments and memorials at this time, but as you can imagine it is very difficult for City staff to choose between who may or may not place a memorial on City property. We are also very guarded against our parks and open spaces becoming full of memorials. Even I, as the Public Art Manager, would not want to see every square inch of public land overrun by artwork. This is not the primary function or intent of public space, but is often a wonderful attribute to public space when and if there is an appropriate piece for a conducive site.

Therefore, we do not wish to discourage your proposal, but do wish to impart to you the above concerns and considerations. I hope you can understand my position, which is that I must be fair and equitable to all residents of Pittsburgh and in doing so must ensure that any time there is a proposal to take a piece of public land for any purpose much scrutiny, public hearing and support must be provided.

Please review the aforementioned concerns, and either email or call at your convenience.

Thank you

Morton Brown

Public Art Manager

Department of City Planning

200 Ross Street, 4th Floor

Pittsburgh, PA 15219morton.brown@city.pittsburgh.pa.us

office: 412.255.8996

cell: 412.901.1546From: Jim Greenwood

To: Morton Brown

Sent: Monday, August 23, 2010, 11:11 PMMr. Brown,

Thank you for taking so much time to talk on the phone yesterday. In answer to your e-mail questions:

Scheney Park is part of the Indian purchase Croghan made in 1749, the 40,000 deed that excluded about two square at the Point for a British fort. The park, Carnegie Mellon campus, and the Blockhouse at the Point became the property of James O’Hara and later donations by grand-daughter Mary Croghan Schenley, whose paternal grandfather William immigrated from Ireland at sixteen under George Croghan’s care. [This information to be added as part of a revised text if a Schenley Park site for the marker is permitted.

.Other than a newly added mention of his name inside Fort Pitt Museum, there is no signage or interpretation for Croghan in Pittsburgh, . This year a PHMC marker was proposed for Point State Park and the location ruled out, first by PHMC for the state marker and more recently by the Parks Department for Monessen’s granite alternative. This will be the first Croghan historical marker in the region.

Although an English major and writer, grammar is of secondary importance to me, at best. Problems with clarity, the facts, or my interpretation will be taken extremely seriously, but so far the criticisms about my historical work have lacked specifics. I would be grateful for any grammatical errors in the text you can point out and where you tripped over my usage. There is only one other active Croghan scholar, history professor William Campbell, who e-mailed the following to me on July 30 when a Point Park site was under consideration:

I have looked quickly at the below text, and think it could use some factual/grammatical revision. The latter might be something is delaying the process. I would be happy to send you an edited version for review, but will need a couple of weeks to get to this. In the meantime, it might help your cause to contact the said individuals below that are considering placing this marker, and mention that you have contacted me and that I have agreed to help revise and edited the marker. Just a thought.”

The edited version has yet to appear, although I have been keeping Campbell up to date with developments for the marker, most recently the image to be etched on it. Any improvements he, you, or anyone can suggest will be gratefully received.

Last I heard, the blue and yellow state markers at Point Park were going to be moved to the parking lot across from the Post Gazette Building. Although I think that is atrocious, I would agree that their ornate and superfluous aesthetic is awful and their ability to convey history too limited. The rationale for a one meter granite square is its intrinsic beauty, dignity, modesty, unobtrusiveness, and ability to convey a a great deal of written and pictorial information. Pittsburgh’s early history can only be understood through Croghan’s story; he was that central to regional events for thirty years. Telling his regional story in 250 words necessitated brevity, allusion, and strict adherence to what happened. Whatever it may be called, Greater Monessen Historical Society is placing a long overdue historical marker for Croghan with subtle memorial and monument aspects, subordinate to establishing his role in the flow of events. While some settings within the city have closer associations with Croghan, Schenley Park is second only to Point Park in offering a somewhat natural setting that suggests Croghan’s time and place to the people most likely interested in the period and appreciative of the information.

Your suggestions for finding better ways to tell Croghan’s story hit sore spots and I apologize for venting frustration. Instead of earning income and accolades for the years of study it took to understand and write regional histories, I’m paying yearly for website ohiocountry.us to make them available and more annual fees for search engines like google and yahoo. There is a page for critical comments on ohiocountry.us where I am also copying the responses to Greater Monessen Historical Society’s request for a site to place the Croghan marker. The story of getting Croghan’s story before the public

more than 200 years after his death has its own historical significance.

Concerns and considerations you e-mailed and spoke about are understandable, as is your position and responsibilities. You are not a historian and must rely on those who are. My credentials, PhD coursework in Literature at Pitt, an MA in Literature and BS in Education/English from California U. of PA are somewhat oblique but not unusual for a historian, particularly when non-fiction and biography are prime interests. Greater Monessen Historical Society’s executive board fully supports my historical work and is comprised largely of professional people, a doctor, a retired teacher and administrator, and two working school librarians, one at the university level. Professor Campbell says he has read my histories on ohiocountry.us and found errors, but so far has forwarded only one minor qualification regarding the Croghan journal I published, which I credited him for in making the revision. Many of our e-mail exchanges are found on the ohiocountry.us Critical Comments page.

One of your other concerns is skeletons in Croghan’s closet. Campbell has done research all over the country looking for them and hasn’t found anything significant, whereas my discovery that Croghan sabotaged the Pennsylvania fort at the forks of the Ohio in 1751 and also betrayed the Ohio Indians by bringing Virginians into their country so that his 1749 deeds would be valid led to sixty years of tragedy in Ohio Country. He probably thought he would remain in control of events and for the next twenty-some years did everything he could to maintain the peace, but that does not alter the bloody events he set in motion. His character and opinions about it are secondary, however, to his role in history. The facts are not in dispute; a little over a century of Croghan scholarship beginning with Darlington has culminated in my work and the breakthrough was not new information. The problem has been psychological, blindness caused by a tradition of Croghan as scoundrel when it is the emperor who has no clothes, to mix metaphors. Washington is the scoundrel when it comes to Western Pennsylvania and Croghan on the whole heroic, a reversal that is greeted with denial and willful ignorance by most professional historians. A sense of humor is helpful regarding Croghan’s story, for its continued suppression is nothing short of ridiculous.

The two most problematic issues that you have raised, skeletons in the closet and confirmation by historians, are not easily resolved and the connection and appropriateness of a Croghan marker in Schenley park is less than for Point Park, where it was denied because of the potential for too many signs in the park. The Harrisburg official who made the decision prefaced it with a hypocritical recognition of Croghan’s importance to our region’s history. It is a ready-made excuse for you if you are inclined to see the Croghan marker as opening the floodgates to Schenley Park looking like a cemetery. There is no one of comparable importance to Croghan in Pittsburgh history, including Mellon, Carnegie, Frick and Westinghouse; no one who has been so unjustly treated and ignored, and no one whose fascinating story is more relevant to the present and future of Pittsburgh. Today’s climate change and mass extinctions endanger that future, for they define the end of ages, the Permian, the Cretaceous, and now ours, and as with Croghan’s story, the truth is an inconvenient but necessary connection to reality. The Croghan marker is important in helping to establish the right side of history and optimism that people can learn its lessons.

It was nice of your to spend so much time talking and e-mailing me about the project, certainly above and beyond the call of professional duty. In a time when many professionals and workers in government are antagonistic to public service, it is heartening to find people who care. It was not true what I said on the phone, that I expected Pittsburgh officials to reject the Croghan marker. I had enough experience to know that the historians at Heinz History Center and the state would be opposed to it, but thought that city officials would be inclined to recognize an important early Pittsburgher even if the national narrative paints Croghan as a scoundrel, unworthy of historical consideration. Heinz History Center finally mentioning him in their interpretation inside Fort Pitt Museum is progress, perhaps a result of my badgering them, yet clearly insufficient. So is the marker for that matter, but it is a good second step and I will be installing it soon, with the approval of you and your colleagues in Pittsburgh where it belongs. I’m sure your decision on the marker will be principled, whichever way it goes.

Best wishes, Jim

From: Dr. Rob Ruck

To: Jim Greenwood

Sent: Friday, August 27, 2010, 8:32 PM—–Original Message—–

From: Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net>

To: ruck439019@aol.com

Sent: Fri, Aug 27, 2010 2:39 pm

Subject: George Croghan historical markerJim,

I’m not that strong on this period of history and would need to spend

hours verifying what’s written, hours that I don’t have right now with

the semester all but underway. I did not see anything in it that I

thought was incorrect but did have a few questions about language.–I’m not sure what you mean by “engrossed Fort Detroit trade.”

–The following sentence is also confusing me: “Celeron’s 1749

expedition reached Logstown a few days after Croghan’s 200,000 acre

purchase, void if in Pennsylvania.”

–I also think that somebody wrote a book recently about this period

and will ask Ted Muller for his name.Good luck with this; Croghan is indeed a lost figure,

RobFrom: Jim Greenwood

To: Dr. Rob Ruck

Sent: Sunday, August 29, 2010, 10:31 AMDear Dr. Ruck,

Thank you for your interest, response, time and especially specific

problems with the text. One of the dictionary definitions for engross is

to acquire the whole of (a commodity) in order to control the market;

monopolize. Fort Detroit at that time was a French trade center suffering

from the British blockade during King George’s War, its much longer supply

route than from Philadelphia or Baltimore, and corrupt Canadian officials.

Other Pennsylvania traders benefited, particularly the Lowry brothers, so

it is a slight exaggeration that I will qualify with “nearly.”Celeron’s expedition claiming the upper Ohio for France, drive out the

the Pennsylvania traders, and overawe the Native Americans was primarily

aimed at Croghan, as his purchase a few days before Fort Detroit’s longtime

commander’s large force of soldiers and Abenaki warriors arrived at Logstown

suggests. About a year later Croghan realized that if his deeds fell into

Pennsylvania, they would be disallowed. Thus he began to aid Virginia,

indispensably in my view, bringing George Washington onto the world stage,

who as Croghan’s rival for influence on the frontier for over twenty years

was behind Virginia’s president judge and Committee of Safety chairman in

Pittsburgh being declared a traitor in 1777 and not being permitted to

return when he cleared himself in 1778. I will work on the sentence about

Celeron and have already revised some of the text to make it smoother. I

deeply appreciate your taking time to point out problems. Historic

accuracy cannot be sacrificed to the need to abstract a long, complex,

misunderstood or ignored story for a marker, nor can clarity. Thank you,

thank you, thank you.Best wishes,

Jim GreenwoodFrom: Colin G. Calloway

To: Jim Greenwood

Sent: Friday, August 27, 2010

Subject: George Croghan historical markerDear Jim:

Thank you for your message. I’m away from the office right now and cannot open

the image on my home computer but I can give you a much better lead. William Campbell

at UC Chico is writing a book on Croghan and has a much more detailed knowledge

than I.Here is his e-mail. wjcampbell@csuchico.edu

Best wishes, Colin

From: Noam Chomsky

To: Jim Greenwood

Sent: Friday, August 27, 2010, 11:06 PMPlease do keep me updated, if it’s not too much trouble. And hope that one of these days I’ll be able to follow it up.

Noam Chomsky

—– Original Message —– From: Jim Greenwood (by way of Noam Chomsky ) To: Noam Chomsky Sent: Friday, August 27, 2010 1:36 PM Subject: Re: George Croghan’s story NC,

Pennsylvania declined placing an historical marker with the following tentative text in Pittsburgh’s Point State Park:

George Croghan (circa 1718-1782)

[etching of his 1749 purchase and map of region]

An Irish immigrant and Pennsylvania fur trader in 1741, during King George’s War Croghan engrossed Fort Detroit trade, fomented an Indian rebellion, and joined William Johnson on the Onondaga Council. He organized and led the Ohio Confederation at Logstown that Pennsylvania recognized as independent of the Six Nations, appointing Croghan colonial agent. Celeron’s 1749 expedition reached Logstown a few days after Croghan’s 200,000 acre purchase, void if in Pennsylvania. Late in 1750 Croghan guided Ohio Company scout Christopher Gist and arranged its Logstown treaty in 1752 after sabotaging Pennsylvania plans for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio.

Ohio Company’s fort was commanded by Croghan’s business partner William Trent and surrendered by half-brother Edward Ward. A captain in charge of Indians under Col. Washington and Gen. Braddock, Croghan could do little to capture Fort Duquesne, but as William Johnson’s Deputy Indian Agent in 1758 he hurried from negotiating the Easton Treaties to his Indian scouts at the head of Gen. Forbes column for its fall. He worked with Col. Bouquet and built the first Croghan Hall, burnt during Pontiac’s Rebellion. Croghan brought Pontiac to Detroit in 1765 and kept the Ohio tribes pacified thereafter, except the Shawnees during Dunmore’s War.

Pittsburgh’s president judge, Committee of Safety of Chairman, and the person keeping the Ohio tribes neutral was declared a traitor in 1777 by General Hand, who prevented Croghan’s return when cleared in a 1778 Philadelphia trial, dashing any hope for the fourteenth colony of Vandalia, with Pittsburgh as capitol and Croghan its Indian agent and largest land owner.

Have asked the city of Pittsburgh to place the marker in its Schenley Park. Will keep you updated on the story of Croghan’s story. Historians find its truth inconvenient, similarly to how the Permian, the Cretaceous, and our age is ending with climate change and mass extinctions. Because Croghan was suppressed and his story continues to be suppressed, it will be some time before it is not relevant. Change is essential and Croghan’s story is a rock that will help break the momentum of the status quo. He was on the right side of history, as you are, and a touchstone for rectifying what’s wrong with the country. If you have a little time please read the blurbs of my printed histories on ohiocountry.us and there is a revealing chronological scholarly summary I provided Pennsylvania in applying for a state marker on the Home page. His is an amazing story, but I know you have too many pressing demands and a worldwide interest in current events to go into its details. It’s a tough time for us here in Western Pennsylvania with the Texas gas well drillers of Marcellus shale teaming with King Coal to make us the nation’s dirty energy capitol. An intense, expensive PR campaign is in progress. Help.

Jim

On Fri, Aug 27, 2010 at 5:09 PM, Marcus Rediker <marcusrediker@yahoo.com> wrote:

Dear Jim Greenwood, Thanks for writing. I am afraid I cannot offer much help here on historical accuracy, but I am cc-ing a couple of people who might: Drs. Van Beck Hall and Peter Gilmore.

Good luck and best wishes,

Marcus RedikerFrom: Alan Gutchess To: Jim Greenwood Sent: Friday, August 27, 2010, 5:29 PM

Mr. Greenwood, I am sorry, but we are in the middle of a large number of our own projects and no one here on staff, including myself, currently has time to vet your text, so I am afraid my answer is “no”. Sincerely, Alan Alan Gutchess Director Fort Pitt Museum Point State Park, 101 Commonwealth Place Pittsburgh PA 15222 412-281-9285 www.heinzhistorycenter.org

From: Molnar, Katherine Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010 9:27 AM To: Jim Greenwood ; Brown, Morton Subject: RE: George Croghan historical marker

Dear Jim,

I am glad you are making contacts with all of the relevant organizations and city departments to start the process of reviewing the installation of this commemorative marker. Please know that letters of support may be sufficient from involved non-profits, but from the City, “approvals” come in the form of public hearings and the issuance of permits. Morton and I will sit down and try to outline all of the steps you will need to take to go through this process, including review by the Historic Review Commission and the Art Commission, and likely permits from public works and/or zoning, and a letter of support from the owner (the City).

In terms of the text, I think it is interesting and shows Croghan to be an accomplished historical figure. However, in my opinion, the text is lacking in interpretation, the “who-cares?” factor. The text is three paragraphs of Croghan’s chronological accomplishments, but does nothing to illustrate why those actions were important. What impact did Croghan have on Pittsburgh? How would today’s world be different had Croghan not been born? How is this text significant and meaningful to the individual reader? A reader should be able to walk away from the marker and remember portions of the text that “speak” to that person directly. I do not believe your text accomplishes this — it is something to consider. Morton and I will try to get back to you in the next few days about the proper process for this review. I am going to be out of the office quite a bit this week, though, so please be patient. Thanks again for keeping me updated, Katie Katherine Molnar Historic Preservation Planner City of Pittsburgh Department of City Planning 200 Ross St, 3rd Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Ph: 412.255.2243 Fx: 412.255.2561 katherine.molnar@city.pittsburgh.pa.usFrom: Jim Greenwood To: Katherine Molnar Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010, 10:00 PM

Dear Katie,

Thank you for the response, but I have to disagree that the text does nothing to illustrate why Croghan’s actions were important. You say that you find the text interesting and that it shows Croghan is an accomplished historical figure. The Pennsylvania official who declined Monessen’s offer to put the marker in Point Park, whose history begins with Croghan’s 1749 deed, prefaced his concern for the potential of too many signs in the park with a recognition of Croghan’s importance to the region. There is a disconnect in both instances that is disconcerting, but typical of the rampant intellectual dishonesty in our society. It is not a conscious lack of integrity, rather psychological denial that expresses itself in cynical non sequiturs.

Croghan’s regional importance in King George’s War, the French and Indian War, and the Revolution are as obvious in the text as the fact that Croghan’s story links events that are of international significance as well as fundamental to the national narrative that begins with 21 year old George Washington’s entrance on the world stage. While the information about Croghan is essentially unknown, nearly everyone knows Washington’s actions in Western Pennsylvania and can see that Croghan’s are more important without me beating them over the head with it.

The image of Croghan’s 1749 purchase of 200,000 acres except for two square miles at the Point and the fact that if the land fell into Pennsylvania it would be disallowed obviously motivated his support of Virginia’s Ohio Company: no other interpretation accords with the facts. The problem is that the current interpretation with Washington at the center of these events does not accord with Croghan’s story, but my saying so in interpreting it will not end the confusion people feel. In fact, just the opposite. As you are doing, they will simply discount my interpretation, whereas if I stick to the facts and arrange them as I have done so that people are forced to face their reality, they will not be able to discount them by blaming my interpretation. If you are honest with yourself, that is what is behind your need for more interpretation from me. It is aimed at reducing and discounting the facts of Croghan’s life and a denial of the subliminal interpretation that makes up their current organization. Best wishes, Jim From: Holly Mayer Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010 12:18 PM To: Jim Greenwood Subject: Re: George Croghan historical marker Dear Mr. Greenwood, It is terrific that you are so deeply engaged in the history of western Pennsylvania in the colonial period. Your work on and in support of George Croghan stands as an example of why we need always to reexamine the past and its interpretations. That said, I’m afraid that I’m not going to be much help to you here, for as you noted, it is the beginning of the semester and I’m swamped. Also, I do not claim expertise on George Croghan and thus cannot corroborate everything you present. Other than that, I can suggest that you edit and shorten the text for the proposed marker so that a casual passer-by would only have to pause briefly to read it, and thus make it more likely that people would do so.

Best wishes,

Holly Mayer Department of History Duquesne University

From: Jim Greenwood

To: Holly Mayer

Sent: Monday, August 20, 2010, 4:29 PMDear Dr. Mayer, Thank you for your response and suggestion. The less is more school of history seems to be characteristic of our era, which by the way is ending as they all have with climate change and mass extinctions, the Permian’s at 95 percent, the Cretaceous, and now ours. As an English teacher, the too much reading excuse doesn’t fly with me. The casual passerby and anyone else can quit reading anytime they wish, but not only is the chore of reading the 300 words grueling, it also requires interpretation and analysis, which a city official in the Historical Preservation department wants me to add. If you get time, check the Critical Comments page of ohiocountry.us, where I’m copying the responses of historians and interested notables, so far Noam Chomsky. Best wishes, Jim Greenwood From: Peter Gilmore Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010 1:52 PM To: Jim Greenwood Cc: Marcus Rediker ; Van Beck Hall Subject: Re: George Croghan historical marker Dear Jim Greenwood,

I’m responding to the email of Marcus Rediker of Aug. 27. You have an impressive command of the life and times of the storied George Croghan and I do not, rendering difficult any meaningful critique or fact-checking. That said, I do have a couple of comments.

Quite rightly the marker makes reference to the fascinating Vandalia episode. Unfortunately, though, the paragraph with references to Vandalia and the treason charge seems somewhat convoluted with the possible loss of some clarity. (I can imagine a reader wondering if it were Croghan himself who occupied each of the listed official posts.) Might it not be possible to explain (albeit in highly condensed fashion!) why Croghan had been charged with treason? Would I be correct in thinking that the treason charge was not unrelated to the war-time threat of a Vandalia secession to the British side, and the competing claims of Virginia, Pennsylvania and Vandalia to the same territory? (My editorial advice would be to sacrifice the Hand reference for sake of a few extra words on the treason charge.)

It is interesting to note, although I suspect well outside the parameters of an historical marker, that in his latter days Croghan competed with that more famous land speculator, George Washington, a former employer, even going so far as to lay claim to western Pennsylvanian land which Washington insisted that he owned.

In that connection, I recall that Washington recorded having attended a dinner at Croghan Hall in October 1770, which of course is consistent (and helps explain) your reference to the destruction of the first Croghan Hall. Would there be any value, do you think, in stating explicitly that the residence was rebuilt following Pontiac’s War, and perhaps identifying its location?

I am confused by the relationship between William Croghan (paternal grandfather of Mary Croghan Schenley) and George Croghan, and I have a good hunch that you’ve handled the matter perhaps as well as can be done, in brevity. My understanding is that there was no relation between the two male Croghans, that William settled in Virginia and later in Kentucky, where he was associated with George Rogers Clark. Was this the case? For my own information, what did it mean for William to come under the care of George? Might it be advisable to state frankly that they weren’t related? (This is a question only, and not a suggestion.)

with best wishes,

Peter GilmoreOn Mon, Aug 30, 2010 at 3:43 PM, Jim Greenwood <green605@comcast.net> wrote: Dear Peter, Thank you for your interest and help. Rob Ruck needed clarification about early sentences. It is quite a challenge to tell even some of the major things Croghan did in a few paragraphs. Croghan was charged with treason because he was a rival of George Washington’s for influence on the frontier since the Fort Necessity campaign, but proof is circumstantial and therefore I had to stick to Washington’s subordinate being responsible for the injustice. Subsequent attacks on the frontier by the British and their Indian allies, see the map of Ohio County on ohiocountry,us and my histories, were the price paid for not allowing Croghan to return to Pittsburgh when he cleared himself at trial. Washington not only had dinner at Croghan Hall in 1770, but like everyone planning a trip down the Ohio came to Croghan for guides and safe passage. Washington’s deed to his Chartier’s Creek holdings was bogus, as Margaret Bothwell discovered, nevertheless he tried to get the fifteen or so families who purchased their land from Croghan evicted in 1784. Kentucky Croghan scholars say William was a nephew, based on letters Croghan wrote to William’s father Nicholas in Dublin that include family information and strong sentiments of love. I am convinced, but am already on the hook for being the first to assert a number of new things about Croghan. Naturally letters between William and Croghan are warm, given George’s paternal role. His daughter Susannah married a British officer who was assigned to Charleston after William was captured there and they hosted and aided William in ways that strongly suggest a family connection. Believe me, I’ve been trying to track down the relationships. The website has a Critical Comments page with e-mails concerning Croghan’s story and the story of Croghan’s story. You are one of the few people willing to discuss it and I appreciate your comments more than I can say. Please make more, if you have time. Best wishes, Jim Greenwood

From: Peter Gilmore Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010 4:31 PM To: Jim Greenwood Subject: Re: George Croghan historical marker Jim,This is great stuff. I’m especially interested in the validity of Washington’s claims to the Millers Run tract. I must confess I am unaware of the Margaret Bothwell reference; could you please give me a citation or otherwise direct me to her discoveries?

My doctoral dissertation (completed in April of last year, although I’m not young) deals with Irish Presbyterian settlement in western Pennsylvania 1780-1830. I didn’t treat the episode of Washington in his squatters in the dissertation, but I will as I revise it for publication. (Although generally described as “Scots” the Seceders whom Washington ejected seem to have been largely of more recent Irish origin. As you will readily recognize, that’s the kind of argument it takes a book to develop!)

I wish you well in your efforts to secure a marker, and hope we can stay in touch.

best, Peter

From Jim Greenwood

To: Peter

Sent: Monday, August 30, 2010, 5:41 PM

Peter, Thanks for your message and interest. This is from my works cited list for “George Croghan: A Reappraisal” and found on ohiocountry.us.: Bothwell, Margaret Pearson. “The Astonishing Croghans.” Western Pennsylvania History Magazine. 48(2) April, 1965: 119-144. She’s one of the few fairly modern Croghan scholars you can trust. The current crop is clueless and most of the ones from her time are worse than worthless. JimFrom: Jim Greenwood To: Katherine Molnar, cc Morton Brown Sent: Tuesday, August 31, 2:12 PM