GEORGE CROGHAN,

A REAPPRAISAL

Jim Greenwood

Copyright © 2009 by Jim Greenwood

The Monongahela Press

25 Mulberry Street

Belle Vernon, PA 15012

George Croghan settled on the Pennsylvania frontier and entered the fur trade in 1741 after emigrating from Dublin, Ireland. Almost nothing is known of his life there. Apparently his father died within a few years of his birth1 and his mother married Thomas Ward, mentioned in 1767 accounts: “To cash paid your father 70.13.0,” “The Balance Paid your Father 69.0.11,” and “By a horse for your father 30.0.0.”² His family emigrated with Croghan or soon after, for half-brother Edward Ward and cousin Thomas Smallman were working for him by 1745.

William Powell and Daniel Clark were kinsmen, Clark an Irish immigrant who became Croghan’s clerk and, after the Revolution, the most prominent American in New Orleans. Dr. John Connolly was Croghan’s nephew and some accounts say that business partner William Trent was his brother-in-law.³ Croghan’s wife would have to be a Wilkins for these relationships to be possible,4 but a questionable source says that she was Hugh Crawford’s oldest daughter,5 perhaps dying when their daughter Susannah was born at Carlisle in 1750.

At age fifteen Susannah married British Lieutenant Augustine Prevost. A half-sister named Catharine, Croghan’s child to Mohawk chief Nickus’s daughter, was born in 1756. Catharine (Adonwentishon) Croghan would become Joseph Brant’s third wife and matriarchal head of the Mohawk Turtle clan still led by her descendants.

Early in 1768 Croghan began caring for a sixteen-year-old Irish immigrant in Philadelphia:6 “William was the son of Croghan’s Dublin agent Nicholas Croghan and was presumably a relative.”7 A July 17, 1769 letter from Nicholas about getting indentured servants and a piper for George begins with his gratitude for finding William a

place with the Shipboy merchants “& kind promise to him,’ concluding “my son John and my Daughters join me in Love to your Honour.”8 Nicholas Croghan also writes that he is supplying money weekly to Mrs. Smallman, likely the mother of cousin Thomas.

If George promised a place in his clandestine trading business after learning commerce from the Shipboys, it explains the nineteen-year-old’s presence at Fort Pitt on August 25, 1771 when he witnessed a power of attorney that George gave Nicholas Croghan. William’s father was to collect debts from two men in Ireland, one of them from Roscommon, the ancestral home of the Croghan clan.9 Landed property in the will of grandfather Edmund Croghan may have been in Roscommon, certainly a better place than Dublin for George to acquire equestrian skill and outdoor hardiness.

Licensed in 1744 and owner of a plot of ground in Lancaster, he traded from a Seneca village at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River, present-day Cleveland, Ohio. Croghan learned Algonquian and Iroquois languages and customs, earning in 1746 a seat on the Onondaga Council,10 the governing body of Iroquois and dependent tribes. Two precedents suggest that securing trade for the Six Nations was the primary consideration.

Some forty years earlier the Seneca had made French soldier and trader Louis-Thomas Joncaire a sachem and in 1742 the Irish trader William Johnson was so honored by the Mohawks. Irish traders James Adair, author in 1775 of The History of the American Indians, and George Galphin achieved similar status with southern tribes, evidence of Irish cultural affinity11 and growing

2

Native American desperation.

King George’s War, declared in March, 1744, reduced the goods reaching French traders at Detroit, raising their cost and creating a vacuum that the always aggressive Croghan filled. French-allied Ottawas, Wyandots, and Twightwees fell under his influence as he pushed his trade west to Sandusky, Ohio and beyond, threatening Detroit and French communications between Canada and Louisiana.

He instigated the Indian revolt against the French in 174712 that became “a springboard for his career: it led to his moving from the Cuyahoga to Pickawillany on the Great Miami; and it brought him forward as a negotiator between the western Indians and the province of Pennsylvania,”13 where his Pennsborough plantation and tanning yard lay a few miles west of present-day Harrisburg. A photograph of George Croghan’s remodeled log house on Condogwinet Creek built in 1742 may be seen on the internet.

It is estimated that “Croghan controlled the activities of probably one hundred men–independent traders, employees, indentured servants, and Negro slaves,”14 about one third of the Pennsylvania Indian trade, earning him the title “King of the Traders.”15 Among Indians he was also the Buck, Anagurunda, lighter of the 1747 Mingo “council fire on the Ohio River, independent of the Iroquois confederacy,”16 as well as the Pennsylvania trader reporting in June that “the Ohio Indians were operating independently of the Confederacy and were in desperate need of supplies.”17

Historian Richard Aquila sees Scarouady as the

3

organizer of the Indians and introduces Conrad Weiser to recommend that Croghan handle the Ohio Indians for Pennsylvania. There is no hint of irony in Aquila’s assessment that “Croghan’s preliminary talks with the Ohio Iroquois went extremely well,”18 not difficult for the Six Nations sachem and successful fomenter of Indian revolts.

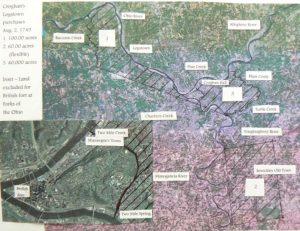

Pennsylvania appointment him a justice of the peace for Pennsborough Township and Indian agent second only to aging Conrad Weiser, but “a momentous event in his life”19 would divide Croghan’s loyalties. “On August 2, 1749, the three most important Iroquois chiefs resident in the area, in return for an immense quantity of Indian goods, confirmed him in the title of 200,000 acres in vicinity of the forks of the Ohio.”20

4

Two square miles of land where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers meet was excluded from the grant for a British fort at the Point.21 A Six Nations response to Celoron’s claim of the Ohio river watershed for France, the deed is dated a few days before the large French and Abenaki party arrived at Logstown.22

Large grants were forbidden in Croghan’s home state, motivating the Pennsylvania trader to help the ostensibly rival Ohio Company claim the area for Virginia where they were permissible.23 Unfortunately, Nicholas Wainwright, Croghan’s most recent biographer, missed the obvious, not acknowledging Croghan’s support of Virginia in its boundary dispute with Pennsylvania until the 1770s.24 Despite contributions such as Fred Anderson’s Crucible of War, Aquila’s Iroquois Restoration, Larry Nelson’s biography of Alexander McKee, scholarship about the era remains superficial because Croghan’s central role in Ohio country events for more than thirty years is unappreciated.

His effectiveness during King George’s War and optimistic nature prevented Croghan from taking the French threat to his trade and land ambitions seriously enough. Celoron’s demand that the Ohio Indians stop trading with the English infuriated them, as did the lead plates claiming their land for France. Only a year after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle restored the pre-war status quo, the French were blatantly violating it.

British trade with the Far Indians was guaranteed by the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick ending King William’s War and the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht after Queen Anne’s War recognized the Five Nations as British subjects. The Crown’s claim to the region rested on the Iroquois conquest of the Ohio Valley during the mid-seventeenth century Beaver Wars, predating French exploration there. Celoron’s expedition, primarily provoked by the King of the Pennsylvania traders and aimed at him, promised war with its shredding of the earlier treaties.

Croghan stockaded Pickawillany in November, 1749 and is credited with building, likely at this time, the earliest remaining structure west of the Alleghenies, the Old Stone Fort at Isleta, Ohio. A November letter from Pickawillany to Pennsylvania’s Richard Peters is significant for more than the influence and confidence Croghan displays:

The Indians hear has received an invitation from

Coll. Cresep & Mr. Hugh Parker to go down to

see the Governor of Maryland which perhaps may

be a detrment to the tread of Pensilvinie as the[y]

want to enter into the Indian tread. I can put a

top to thire going down if you think it

convenent.25

It is possible, barely, that Croghan did not know Thomas Cresap was a key member of the Ohio Company of Virginia and Parker a company agent, but the crucial aid he would begin giving Virginia a year later was grounded in his Indian grant, not his credulity.

Late in 1750 it was only by mentioning Croghan’s name that Ohio Company agent Christopher Gist escaped harm from Virginia-hating Ohio Indians at Logstown, where he and Croghan were to have met. Croghan and Andrew Montour had gone ahead to the Wyandot town of Muskingum. When joined by Gist, they conducted him on a tour of Indian villages in the Ohio country, supposedly unaware that “Gist was searching for lands suitable for settlement by the Ohio Company, a subject he dare not mention to the Indians or the traders.”26

Wainwright also fails to credit Croghan for orchestrating the incident whereby Pennsylvania “defaulted its leadership in the West to Virginia’s Ohio Company.”27 Early in 1751 Croghan wrote Thomas Penn that the Indians were asking for a strong house on the Ohio. An enthusiastic Thomas Penn wanted one built of stone under Croghan’s direction and ordered Governor Hamilton and Secretary Peters to confer with him to get it erected even “if the Assembly refused to sanction the fort,”28 an unlikely event despite the Quaker dominated Assembly’s reluctance to “countenance the idea.”29 At a Logstown conference in May, Croghan recorded the Indian spokesman’s request for the fort, as Penn ordered.

“Gloomily, the Assembly called in Andrew Montour to testify,”30 but to their astonishment, Croghan’s interpreter at the treaty said that the fort was Croghan’s idea and doubted that the Indians would consent to it, ripping Croghan’s “reputation to shreds.”31

Governor Hamilton was offended, complaining that he and the province had been imposed upon. Croghan demanded a hearing, offered to bring down the Indians and traders at the conference, and had Montour sign a retraction, but “no one was convinced by the interpreter’s about-face.32 Wainwright’s obtuse conclusion that Croghan’s “moment had passed”33 is misleading and curiously naive.

Wainwright’s short-sighted analysis of the reverses to Croghan’s trading empire in 1751 again misses the point. Biographer Albert Volwiler attributes the cause to French and Indian depredations, Wainwright to Croghan and Trent’s heavy borrowing and over-expansion, and while both views are valid, the larger picture is of an economic boom and bust cycle with Croghan at its center, primarily responsible for the bubble’s over-supply.

Largely due to Croghan interdicting French trade, “the year 1750 produced a bumper crop of skins,”34 cutthroat competition, and ruin for everyone in the fur trade when the market collapsed. Croghan’s assets were frozen by creditors and Richard Peters foreclosed his mortgages on Croghan’s Pennsborough holdings, forcing the Irishman and partner William Trent into Indian country to escape debtors’ prison.

As part of their campaign to drive English traders out of the Ohio valley, the French offered “one thousand dollars for”35 Croghan’s scalp. On June 21, 1752, French and Indians under Charles Langlade attacked the Twightwee village of Pickawillany, “cooking and eating Memeskia, the old Miami chief known to the French as La Demoiselle and given the name Old Briton by Croghan.”36 If the Croghan-arranged Twightwee alliance with the English has meaning, the attack was the opening engagement of the Seven Years’ War.37

Old Briton’s demise came as, “our brother, the Buck”38 conducted Virginia’s June, 1752 Logstown conference granting the Ohio Company permission to settle west of the Alleghenies and “requesting the

8

Virginians to build a fort at the forks of the Ohio,”39 Andrew Montour translating. Croghan no longer represented Pennsylvania, as the Half King made clear to Virginia’s delegation, for “he is one of our people and shall help us still & be one of our council.”40

At about this time, Croghan purchased 4,000 acres from the Six Nations on Aughwick Creek 40 miles west of Carlisle to replace the Pennsborough plantation as the new eastern terminus of his rapidly constricting trading operation. An Indian country refuge from his creditors, it would soon become a dangerously exposed frontier fort during the French and Indian War, which, as Anderson in Crucible of War suggests, Croghan had the leading role in starting.41

Croghan’s forwarding of Ohio Company interests becomes more obvious with the appointment of his partner, William Trent, as factor in 1752. The following year Trent was ordered to build the fort on the Ohio River, a storehouse at the mouth of Redstone Creek on the Monongahela River, and a wagon road there from the Ohio Company’s storehouse at Wills Creek, Maryland.42 When the stockade on the Ohio fell to the French in April, 1754, it was surrendered by Croghan’s half-brother, Ensign Edward Ward.

At the end of May, Croghan contracted to supply flour for Washington’s troops marching against the French at the Forks of the Ohio and on June 1st, Ohio Company member and Virginia’s Governor Dinwiddie appointed him interpreter for the expedition, in charge of Indian affairs,43 assisted by Andrew Montour. A few days earlier on May 28, 1754 the Half King, as the Six Nations

9

overlord of the region was known, tomahawked wounded French officer Jumonville who had surrendered during Washington’s surprise, early morning attack.

It had been only five months since the Half King, Guyasuta, and other Indians had accompanied twenty-one-year-old Washington, Christopher Gist and three of Croghan’s men to Fort Le Boeuf with the same sort of summons Washington was reading when Jumonville and all but one of the wounded French were killed and scalped. Croghan’s presence might have prevented the mayhem and Washington’s rash breach of the peace. The Cherry Tree myth grew out of his misrepresentations of the incident, including when he learned of the French summons,44 that he commanded only 40 men,45 and did not know what assassinate meant in the Fort Necessity surrender terms.

Washington rebuked Croghan for late, inadequate delivery of flour to his hungry men and for involving “the country in great calamity”46 by vain boasts of influence with the Indians. Native American allies said Washington treated them like slaves and wouldn’t listen to their advice, as a year later they would say about Braddock, who told them they would have no land rights when the French were defeated. Still Croghan managed to retain eight Indians for Braddock, minus viceroy Scarouady’s son, shot by a frightened British sentry, but could convince none to fight under Washington in 1754.

Croghan was at Christopher Gist’s plantation for Washington’s negotiations with the Delaware and Shawnee living near Fort Duquesne. Having seen the French forces and supplies, they would not join

10

Washington’s over-worked, inadequately fed, and under strength ranks. The Half King and Queen Aliquippa took their people to Maryland, followed by Croghan with Washington’s order to bring back the warriors. They would not return and if any were at Fort Necessity, they left with Andrew Montour and Croghan’s men the morning of the battle, perhaps as Washington was dressing the ranks of his exposed soldiers on the Great Meadow.

Croghan returned to Aughwick with the Indians, as he would a year later, after Braddock’s defeat in 1755, with Charles Langlade leading the French Indians in both engagements. Washington’s courage during the battle on the Monongahela and loyalty to the stricken general are well know facts, but Croghan was there too, close enough for the general to reach for the Irishman’s pistols to try suicide, and on the night ride to inform Dunbar, he rode beside Washington. After the debacle, Pennsylvania commissioned Croghan to build a string of forts to protect the frontier, including one at Aughwick he called Fort Shirley, after the new British commander.

Appointed Deputy to Northern District Indian Superintendent William Johnson in November, 1756, it was a position he would hold for sixteen years. Croghan commanded one hundred Iroquois who watched waves of British regulars cut down in frontal assaults on Fort Ticonderoga. There was no such slaughter when Fort Duquesne fell in 1758 because Croghan had deprived the French of their Delaware and Shawnee allies in a series of treaties held at Easton, Pennsylvania. Croghan and his Indian scouts headed the Forbes column that captured the

11

French fort, a deserted, blown-up, smoldering ruin.

As Fort Pitt was being built by his companion during the Braddock expedition, Captain Harry Gordon, Croghan fed, clothed and gave presents to Indian visitors, gathered intelligence, and built a house four miles up the Allegheny on its eastern bank, not across the river “at his old Pine Creek plantation”47 where Wainwright mistakenly places Croghan Hall.

Croghan’s house was looted and burnt during Pontiac’s Rebellion, as was the Sewickley Creek trading post where his partner Col. Clapham was murdered. More than the Indians, Croghan blamed General Amherst for ignoring his warnings and the intelligence he gathered. His devastating losses did not prevent critics, aware of Croghan’s influence with the Indians, from accusing him of complicity in Pontiac’s Uprising.

He journeyed to London early in 1764 where his efforts to confirm his Indian deeds and gain restitution for himself and the “suffering traders” of 1754 and 1763 were frustrated.48 “After two ineffectual months in England, Croghan wrote Johnson, ‘I am sick of London & harttily tired of the pride & pompe of the slaves in power.'”49 He quickly came to view both Whigs and Tories as rogues, members of the Board of Trade as “imensly ignerant,” their words “meer froath,” and observed that “The cheefe study of the people in power hear att present is to lay heavy taxes on the colenys. . . .”50

Croghan’s complaint of the London elite’s neglect of “public affairs for private concerns”51 might seem hypocritical given his semi-secret trading and gargantuan land speculations, were they not matched by his

12

dedication to public service, the reason the Indians entrusted him with huge purchases, why the Crown employed him as its chief negotiator for sixteen years, and the basis for his being nearly universally esteemed.

Life in London for Croghan was that of a well-dressed gentleman with a fashionable address, liveried servant, and private carriage. More evidence of a higher class background for Croghan than currently accepted appears in the record at this time, making his London stay and career in America less fantastic. “Croghan had intended to go to Dublin, where he hoped as the heir of Edmund Croghan, his grandfather, to recover landed property,”52 but in the end he hired an attorney as months went by in London waiting for the Lords of Trade to take up Indian affairs.

When they did, the Board denied his petition to relocate his 200,000 acre Indian purchase to New York’s Mohawk Valley and tabled his proposal to plant a colony in Illinois to help secure the frontier, but his suggestions to reorganize the Indian department and advance the Proclamation Line of 1763 from the Allegheny watershed to the Ohio River were tentatively approved. There would be no French money for suffering trader loses, only the prospect of Indian land in the newly acquired territory as reparation. Croghan set sail for New York in September, having learned a more “gracious, luxurious way of living.”53

Johnson ordered him to help Bouquet in Ohio, but Croghan tarried in Philadelphia, purchasing and lavishly furnishing a newly built brick house he called Monckton Hall after the British general. A silent partnership with

13

Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan to win the Illinois trade from the French was established. With “Ł20,000-worth of Indian goods for the western trade”54 promised, Croghan returned to New York where a relieved General Gage accepted Croghan’s offer to pacify the Illinois tribes.

Peace and trade with the Ohio Indians had to be established first. Croghan accomplished that preliminary in May, despite violent opposition by the Conococheague Black Boys, and began the river journey to Illinois country. Three of the ten Shawnee accompanying the Illinois expedition were killed when eighty Mascouten and Kickapoo warriors attacked Croghan’s camp six miles below the Wabash. “Croghan was tomahawked, two of his servants killed, and nearly all the white men were wounded,”55 before a wounded Shawnee chief’s threats halted the massacre.

By the time the Illinois Indians had carried their loot and prisoners to Ouiatenon, they were begging Croghan’s forgiveness, fearing war with the Shawnees. “In July, Pontiac and deputies of the four Illinois nations met Croghan in council in Ouiatenon and agreed to let the English take over the French posts in Illinois”56 Croghan credited his success to the hatchet blow he received and his survival to his hard head.

Depositing Pontiac at Detroit, Croghan traveled to Johnson Hall to report, then to New York to persuade General Gage that the charge of issuing illicit passes for trade goods burned by the Black Boys was unfounded. General Gage was not only willing, but eager to forget the matter, but Croghan would have none of it.

Colonel Bouquet, promoted to general and sent to

14

Pensacola where he died of yellow fever, had stressed the Indian agent’s culpability, yet in the letter Croghan produced, Bouquet was “requesting him to take the merchants’ goods and pass them as the king’s goods.”57 Bouquet may have been referring only to the crown’s present for the Indians, but Gage reacted otherwise, throwing up his hands and exclaiming, “Oh! my God! What is all this? Mr. Croghan you are a most injured man.”58

Samuel Wharton joined Croghan in New York, where violent demonstrations against the Stamp Act earned the peace-maker’s disapproval. Together they rode to Philadelphia, stopping at Burlington where New Jersey Governor William Franklin was drawn into the Illinois speculation. As a teenager, Benjamin’s son had accompanied Croghan and Conrad Weiser to the 1748 Logstown conference.

After adroitly winning over his former foes in the Pennsylvania Assembly, Croghan made the Johnson Hall, New York, Philadelphia circuit once more, enlisting Sir William as a partner, General Gage’s approval to travel to Fort Chartres, and about Ł4,000 worth of goods from Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan.59

At Fort Pitt awaited a delegation of Indians anxious to avenge the murders of some of their people in Virginia and Pennsylvania. Although Croghan succeeded in quieting the Ohio tribesmen, “Never had he experienced so much difficulty in persuading their warriors not to commit hostilities.”60 A conference with Shawnees at the mouth of the Scioto was equally difficult, but Croghan convinced them not to avenge their chiefs killed by the

15

Illinois tribes the year before.

When he reached Fort Chartres, Croghan held two conferences, the first reconciled the Shawnees and Illinois tribes, and the second with the Illinois affirmed a general peace, gaining their promise to trade with the English and sell them land. A recurrence of malaria forced Croghan down the Mississippi to New Orleans, where he took ship for New York, arriving in January, 1767. After settling some affairs, he returned to Monckton Hall to recuperate and write his reports before journeying to Johnson Hall in March.

In May he was ordered to Fort Pitt, where he resolved more Indian complaints of murders and of whites settling on their land. Returning to Philadelphia, Governor Penn questioned Croghan about the Indians who were to accompany Mason and Dixon on their survey. Penn wrote, “It would be very difficult to manage this business without his assistance.”61 Indeed, the Indian guides stopped the survey 36 miles short of its terminus, presumably on Croghan’s orders.

Hugh Crawford was Mason and Dixon’s Indian interpreter, about whom Harold Frederic and William Frederick write:

Totally unmentioned in extant Westsylvania

literature is the real enough fact that the

Kittanning Indian Trader, Old Hugh Crawford,

actually pacified his old friend Pontiac and had

to conduct the Ottawa Indian War Chief to meet

with the British Superintendent of American

Indian Affairs, Sir William Johnson (a distant

16

cousin of Pittsburgh’s Trader King George

Croghan who was Crawford’s son-in-law), to the

historic meeting at Oswego, New York.62

When the authors mention “Old Hugh Crawford and his brother-in-law, the very colorful Andrew Montour,”63 their “very real facts” are not referenced and William Trent’s role usurped when they say that from 1758 until his death in 1770, Hugh Crawford “was the chief administrator of his son-in-law George Croghan’s far flung mercantile empire,”64 assisted by a “princeling” in that empire, John Crawford, only son of Hugh’s nephew William Crawford.

Sir William Johnson, Hugh Crawford and Andrew Montour join William Trent as intimate associates of Croghan who some sources say were related. Trent became Croghan’s business partner in 1745 and was one of his Indian Affairs assistants, often acting as secretary at conferences with Thomas McKee translating, until Trent left the Indian service in 1760 when fur trading resumed.

Trent’s replacement was McKee’s son Alexander, whose mother Mary had been captured as an infant by the Shawnees and who taught her son their language and customs. Alexander McKee would marry a Shawnee woman, also likely a white captive, and become one of the cultural mediators who invented the Ohio Frontier, as Chapter One of Larry L. Nelson’s McKee biography convincingly argues. A Man of Distinction Among Them also offers insights into Croghan’s intelligence gathering network and trading operation.

In addition to McKee, Croghan hired his half-

17

brother Major Edward Ward and Thomas Hutchins as assistants: “he uniformly surrounded himself with men of exceptional ability.”65 With the aid of his red and white relatives, friends, and associates, Croghan wielded enormous influence on the events that shaped the frontier, but ultimately they were as much out of his control as his finances.

His 200,000 acre Indian grant blinded him to the consequences of supporting Indian-hating Virginia’s claim to western Pennsylvania and he may have known that in 1752 surveyors for Pennsylvania had confirmed that Logstown was within its charter. Still, he thought that Pennsylvania’s western boundary was twenty miles east of Fort Pitt, believing that there were only 48 miles in a degree of longitude, a misconception mentioned in a 1771 letter to Croghan from James Tilghman citing Mason and Dixon as authorities for a degree containing 53 miles.66

By the time of Tilghman’s letter, Croghan was bankrupt from enormous land purchases and the expense of establishing a plantation on the New York frontier. On June 27, 1767 he had petitioned New York Governor Moore for forty thousand acres on Lake Ostego, granted on July 6th. Aside from frequent trips to New York on Indian affairs, most of the summer was spent with ailing William Johnson. General Gage responded to unsettling reports from western outposts of a new Indian conspiracy by sending Croghan to Detroit to investigate.

Going by way of Philadelphia, Croghan and Wharton organized a campaign to convince London authorities that unless the new boundary line was run, war

18

with the Indians was inevitable. At Fort Pitt, confusion and exasperation reigned among the Indians. Croghan spent a week counseling with them and at Detroit, “ten busy days reproaching the Indians for their bad behavior and settling differences between the commissary and the traders.”67 His return to Monckton Hall brought a summons to appear before the Pennsylvania Assembly, which joined the lobbying effort to have the new boundary line run.

General Gage read his report on the Detroit mission and no sooner had he been debriefed then a new crisis arose, ten Indians murdered on the banks of the Susquehanna River by Frederick Stump and his servant. To prevent a trial in Philadelphia, the Paxton Boys freed the culprits from Carlisle jail at high noon. “Crippled with rheumatism, which was to be a chronic winter complaint from now on,”68 Croghan traveled to Philadelphia, advising the bickering Assembly to allocate Ł2,500 in condolence money.

As he was about to begin his journey to Fort Pitt, word reached Croghan that the Paxton Boys intended to waylay and kill him. A military escort was ordered to meet him at Lancaster, but Croghan was so concerned about an Indian attack that he went ahead through a snowstorm without them. An observer of the subsequent treaty “wrote: ‘Col. Croghan has been indefatigable & never displayed his great influence and address with the natives, more signally and successfully.'”69 Less successful were Croghan’s attempts to deal with his creditors and raise money for his speculations.

Among Croghan’s papers from this time is a 1768

19

tavern bill that includes the toasts he made:

16.12.6 total. 40 bottles of whisky 10.2.4, 4

bottles of Punch 0.12.0, tuare[?] bear [beer] 0.3.0,

glasses broke 1.06.0, 30 gentlemen’s dinners 3.0.0,

music and bowls of punch 1.5.0 gentlemen 2

bowls of punch 1.4.0. 1st toast- “F, rom evry

gen’rous noble passion free / A, s proud and

ignorant as man can be / R, evengefully avaritious,

obstinate is his / M, alicious, stupid, obdurate will

loss be / A, ffecting consequence he dully grave /

R, est here my pen enought – the man’s a Knave.

First toast: “May we never want courage when put

to a shift. 2. May the friend we trust be honest

– the girl we love be true & the country we live in

be free. 3. The heart of friendship and the soul

of love. 4. May we kiss whom we please and

please whom we kiss. 5. The charitiable hand that

guides the blind. [6.] the Charitable — that

cloathes the naked, feeds the poor & sends the

Proud Empty away. 7. The female Chim[?] is

“to.” 8. days of Ease & Nights of Pleasure. 9.

Days of sport & nights of transport. 10. The

whole that makes two holes merry.70

The sentiment regarding farmers adds piquancy to Croghan’s frequent complaint that he would rather be one, at the tail-end of a plow on the frontier, than continue his thankless work as an Indian agent.

His position gave him an inside track on land purchases, however. In attendance at Johnson Hall for

20

Henry Moore’s purchase of Indian lands in June, Croghan bought 40,000 acres for himself, as well as large tracts for William Franklin, Joseph Galloway, Thomas Wharton, British army officers, and wealthy New York speculators. When the sale was completed, Croghan, Wharton, and Trent met ailing William Johnson in New Haven to insure his cooperation at the 1768 Fort Stanwix Treaty. Prior to it being signed, Croghan bought huge tracts of Indian land for friends and 127,000 acres for himself.

Croghan’s influence with the Six Nations is found in their conditions at the Stanwix treaty: that their preliminary sales be approved by the Crown, that Trent and the “suffering traders” be given 2,500,000 acres, and “third, should the Penn’s seize the 200,000 acres which the Indians had granted ‘our friend Mr. Croghan long ago,’ they requested that the king grant Croghan as much land elsewhere.”71 Eventually the Board of Trade would reprimand Johnson and disallow private grants, threatening Croghan’s Lake Otsego purchases from the Indians as well.

Desperate to patent more than a quarter million New York acres before the ruling took effect, Croghan drew large bills on Samuel Wharton in London and gave personal bonds for part of the patent payment, fully aware that Wharton was as short of funds as he. Hope that Wharton would be able to sell some of Croghan’s western lands sustained the Indian agent, as did the possibility that the Crown might reverse its refusal to allow the Fort Stanwix land grants and sales. Threats of an Indian war had spurred London to make the boundary extending treaty and might work again for the land speculators, if

21

validated by Sir William.

Unable to sit a horse because of his gout, Croghan rode to Johnson Hall in a wagon to gain support for the plan, but it was denied. “Disappointed, Croghan wrote to Wharton, likening Sir William to Dr. Slop in Tristam Shandy.”72 Lawrence Stern’s long, learned, recently published novel may have distracted Croghan as he lay bedridden in Croghan Forest, but even if not, his use of literary allusion is incompatible with a view of the Indian agent as illiterate, one of Bouquet’s often quoted charges.

If Trent, Wharton, and Croghan’s attempts to blackmail London with threats of Indian attacks appear cynical, they were not mere fabrications. Soon after refusing to write to London about serious trouble on the frontier, Johnson ordered his lame deputy, bedridden in New York, to pacify the Indians threatening Fort Pitt. With General Gage’s permission, Croghan sent Alexander McKee to placate them and promised to treat with them in the spring when they would have winter furs and skins to trade.

A painful journey to Philadelphia could not be avoided, however. Confined by illness to Monckton Hall and under siege by creditors, he “did his best to satisfy them all without giving them any money.”73 To escape the dunning Croghan returned to his New York sickbed, where, suffering like a saint in reports by visitors, he “proposed plans to convert the heathen and promoted church affairs.”74 Spiritual considerations were soon put aside as land speculation consumed Croghan’s attention.

Even as he lost huge tracts of land to creditors, he acquired the 18,000 acre New York township of

22

Belvidere, again giving his bonds for patent fees. But in February, 1770 the bills on Wharton were returned for nonpayment and he lost all credit. Some of those owed money followed him to remote Croghan Forest, where “news of his arrival brought whites and reds flocking to his hospitable board.”75 By May he was planning a short business trip to Fort Pitt, arriving there July 2 in a chaise still unable to ride a horse, but the numerous lawsuits filed in eastern courts made returning inadvisable and Croghan Hall was his home for the next seven years.

Due to the Townshend Acts, Croghan found Indian affairs worse than in 1769. British trade goods were boycotted and in place of the necessities to feed and clothe Indian families, traders offered rum for skins and furs. “The Indians were consequently more debauched than ever, behaved badly, and, when not murdering their own people, were being shot by frightened white men.”76 Virginia settlers on Cheat River and Redstone Creek would have been attacked and driven over the mountains had Croghan not intervened to tighten controls on rum and appease the Indians, earning the praise of Captain Charles Edmonstone, commander of Fort Pitt.

Capt. Edmondstone had reason to again commend Croghan in the spring of 1771 when the Indian agent exposed and defused an uprising planned by a confederacy of Ohio tribes, southern nations, and Senecas. Peace was essential if Samuel Wharton’s petition for twenty million acres for a new colony was to succeed in London. “Pittsylvania, or Vandalia, as the colony was later called, included within its bounds both Croghan’s Indian grant and the Indiana grant and

23

guaranteed their titles,”77 but Croghan did not wait for confirmation.

He opened a land office to raise extra money for pending legal action by creditors in New York, Bedford, Carlisle, Lancaster, and Philadelphia, as well as to maintain his Croghan Forest plantation, Monckton Hall, and Croghan Hall. His meager Indian agent salary, £200 a year, did not cover the department’s expenses, nor at times did the returns from his interests in the fur trade.

According to Crawford genealogist Harold Frederic, Washington bought a subtract of Croghan’s Youghiogheny River property that “Valentine Crawford developed into a 1,500 acre plantation for the Great Virginian,”78 present day Perryopolis. William Crawford surveyed the ground in 1767, two years before it was open for settlement, evidence that Frederic is correct about the purchase. Less likely is his assertion that the Crawfords’ land at Stewart’s Crossing was part of Croghan’s 60,000 acre grant,79 although the deed had a provision for flexibility.80

George Weddell settled on the terrace across the Youghiogheny River from Croghan’s Sewickley Creek trading post in 1758 and young Joseph Hill built a cabin not far southward in 1754. While the latter may have made a tomahawk claim, Weddell was surely among the early purchasers of Croghan’s grant. He may have been one of the three men who brought the news to Fort Pitt of the murder of Colonel Clapham when the Delawares burned the Sewickley trading post in 1763.

Not only did Croghan’s 1771 land office continue to sell property from his still unapproved 1749 grant, but

24

tracts outside it. His share of the Indiana Company grant was only 23,852 acres, yet “Croghan sold 100,000 acres.”81 He also refused to pay Pennsylvania taxes, as the colony in competition with Virginia extended its rule beyond the Alleghenies after the Stanwix Treaty.

Vandalia, encompassing most of West Virginia, southwestern Pennsylvania, and eastern Kentucky, would restore Croghan’s fortunes, but delay followed delay. In the summer of 1771, Wharton wrote Croghan to gather petitions supporting the project and to warn London that an Indian war would result from further procrastination: “‘Nothing will do but to act as you and I did about the boundary line. Mens passions must be alarmed and awakened.”82 Croghan complied, and to better serve Vandalia, resigned from the Indian service on November 2, 1771.

Sir William appointed Alexander McKee as temporary Deputy Agent, until Croghan’s private matters were settled. He “remained on call when Indian affairs were critical. Indeed, the native chiefs preferred to treat with him and Croghan Hall continued to be an Indian haven.”83 Things changed only superficially, the loss of his Ł200 annual salary more than balanced by a fur trading partnership with cousin Thomas Smallman that at last made Croghan Hall a legal trading post.

“Barnard and Michael Gratz had become Croghan’s principal agents, creditors, and suppliers in the fur trade,”84 as well as trusted friends. Croghan’s heirs in nineteenth century lawsuits would claim that the Gratzes abused Croghan’s trust. The fact that they were unable to sell his New York lands at any rate and he could not free

25

himself of debt lends credence to the charge, as does the immense fortune they made after Croghan’s death from the huge tracts he had signed over for them to sell.

Despite gout and other ailments limiting his writing to friends, General Gage put the best building at Fort Pitt at Croghan’s disposal in 1772 when the garrison was withdrawn.85 Eventually the fort was demolished, except for Bouquet’s 1764 Blockhouse. The structure remains as Pittsburgh’s oldest building, a gift in 1895 to the Daughters of the American Revolution by Mary Elizabeth Croghan Schenley, granddaughter of William Croghan.

Croghan Hall and Croghanville, not far from today’s Heinz History Center on [cousin Thomas] Smallman Street, no longer exist, and the region’s most influential early resident has yet to be commemorated. Not so Croghan’s Jewish friends, the Gratz brothers, for whom Gratztown is named, the Youghiogheny River village on or near the site of Croghan’s trading post at the mouth of Sewickley Creek.

As during Pontiac’s rebellion in 1763 when his trading partner Colonel Clapham and four others were murdered by Delaware Indians there, a similar outbreak was expected when the Fort Pitt’s British garrison withdrew in 1772. Pittsburgh was more dependent than ever on Croghan keeping the peace with the Indians, despite his resignation as Johnson’s Deputy.

He no longer had the services of old friend Andrew Montour, killed by a Seneca house guest in January, 1772, so Croghan sent McKee to tell the Ohio tribes that the British troops had left Pittsburgh to please them. A second message soon followed when Vandalia

26

was at last approved by King George and Croghan was ordered to alert the Indians.

Autumn brought “one hundred Wyandots, Ottawa, Chippewa, and Delaware chiefs”86 to Croghan Hall for a meeting with the new colony’s governor and to receive presents, but Samuel Wharton did not come. Croghan’s winter provisions were soon consumed. He borrowed money, pawned his plate and other valuables to feed and buy presents for the four hundred Indians who attended his November treaty concerning Vandalia, spending Ł1,365 on the doomed colony.

In the summer of 1773, Lord Dunmore visited Pittsburgh and as Virginia’s governor recognized Croghan’s 1749 Indian grant. Dunmore appointed Croghan’s nephew,87 Dr. John Connolly, his western agent. “With Croghan’s full support, Connolly claimed Pittsburgh for Virginia in January, 1774, and called up the militia. The first man to appear on the parade ground for the initial muster came from Croghan Hall.”88

Connolly appointed Croghan relatives Edward Ward and Thomas Smallman as magistrates and when Governor Dunmore appointed justices of the peace, Croghan’s name headed the list. Pennsylvania tried to continue its five year administration of the region through agent Arthur St. Clair amidst growing confusion. “Flushed with self-importance, Connolly became increasingly arbitrary and high-handed,”89 toward St. Clair and Croghan.

In the spring of 1774 a series of brutal murders by Virginians inflamed the Indians and Croghan hired one hundred men to protect settlers, cooperating with St. Clair

27

and the Pennsylvania partisans to defend the frontier. Connolly informed Lord Dumore that Croghan had switched sides and was now working for Pennsylvania in the border dispute and was inciting the Indians to attack Virginians.

The Senecas and Delaware did not want war and were quickly neutralized by Croghan. Shawnee chief Cornstalk also wanted peace and ordered three chiefs to escort the traders in his country to Croghan Hall. Connally sent forty militiamen to arrest the chiefs, who escaped across the Allegheny River, were pursued, and one of them shot. All summer Croghan held conferences to prevent a general war, largely at this own expense, but Dunmore’s animus towards the Shawnees continued.

“In August, deputies from the Six Nations arrived with a great council belt for Croghan and McKee, announcing the death in July of Sir William Johnson.”90 He had died the day before 50,840 acres of Croghan’s New York lands were auctioned at a sheriff’s sale, depressing the bidding which nevertheless totaled Ł4,840. Much of the purchase price was never paid and only Ł900 was applied to Croghan’s debts, the sheriff absconding with the rest. Borrowing Ł6,000 in Virginia, Croghan secretly purchased 1,500,000 acres of Allegheny River Indian land, to take effect when they vacated it.

Dunmore’s arrived in Pittsburgh in September to prosecute his war and investigate Connolly’s claim that Croghan had incited the Shawnees and sided with Pennsylvania against Virginia. Croghan easily disproved the charges and was appointed president judge when Dunmore moved Virginia’s Augusta county court to

28

Pittsburgh.

In May, 1775, after the battles of Lexington and Concord, a West Augusta committee of correspondence was created in Pittsburgh with Croghan as president. Arthur St. Clair presided over a rival Pennsylvania committee at Hannastown. A month later, at the beginning of a treaty at Croghan Hall to ratify the peace after Dunmore’s War and to establish relations with the revolutionary government in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvanians arrested Connolly in Pittsburgh and jailed him at Hannastown. “Croghan and his committeemen penned so spirited a letter to the Hannastown group that they promptly returned the captive.”91

Connolly soon left town to join Lord Dunmore on a British man-of-war in Chesapeake Bay, where the two planned a military campaign to capture Pittsburgh and split the northern and southern colonies, but the plot unraveled when Connolly was captured by Maryland patriots and jailed. As these events were unfolding, Croghan secretly bought from the Six Nations six million acres between the Beaver and Allegheny rivers on July 10, 1775, with the same provision as his 1773 purchase, that the land was not to be settled until after the Indians left.92

A few days later, June 12, the Continental Congress organized an Indian department and appointed Indian trader Richard Butler as its Pittsburgh agent. When Butler announced his retirement the following April, Croghan sought to replace him through a recommendation of Pittsburgh’s Committee of Safety, which he chaired. “It must have been a severe blow to his

29

pride when the position went to George Morgan. Indian agent Morgan had absolutely no use for Croghan. When he wanted advice, he called on McKee.”93

Learning that McKee had received a letter from the British commander of Fort Niagara, Croghan’s committee put him on parole not to leave Pittsburgh or do anything inimical to American interests. Then, early in 1777, recognizing that Morgan relied on McKee in dealing with the Ohio tribes, Croghan allowed his former deputy to accompany the new agent on a visit to Indian country, bringing all three under suspicion of loyalist activity.

Distrust of Croghan by the authorities in Philadelphia has been characterized as a reaction to a new round of questionable land dealings in his effort to pay off nearly Ł24,000 in debts, “his fifteen years as an officer of the Crown, and the fact that his son-in-law was on active duty with the British army.”94 During the summer of 1777, Croghan visited Williamsburg with the Gratz brothers to clear the title for land he had sold them and to discuss the frontier’s defense with Governor Patrick Henry. Denied the land title, he returned with dispatches from Governor Henry for General Hand, commander of Fort Pitt, to find himself under suspicion of a “horrid” loyalist conspiracy. Alexander McKee, Simon Girty, and others had fled to British Detroit.

In Croghan’s absence, General Hand seized and examined the papers of cousin and business partner Thomas Smallman. Nothing disloyal was found, yet Hand ordered the elderly, ailing Chairman of Pittsburgh’s Committee of Safety to move to Philadelphia. William

30

Trent in a letter to Barnard Gratz wrote, “I am sorry the People were so foolish as to use Col. Croghan so ill, as, to force Him to go to Philad.,”95 but it was not “the People” ignoring his patriotism and irreplaceable influence with the Ohio Indians that had kept them neutral and the frontier protected.

Correspondence between Hand and his superior regarding Croghan has not survived, but it is inconceivable that Washington was not involved. His antagonism towards his frontier rival dated to the 1754 Fort Necessity debacle, intensified in 1772 when their dispute over mutually claimed land in the Chartiers Creek watershed became bitter, and is the best explanation for the accused Tory Croghan being ordered to Philadelphia when it was about to be captured by the British.

Two weeks after his return to Monckton Hall, accompanied by clerk John Campbell and servant James Forrest, Philadelphia fell to General Howe’s redcoats. “Croghan, bedridden again with gout, could not escape. Howe promptly called Croghan to headquarters and berated him for serving as a committeeman in Pittsburgh and for neutralizing the Lake Indians.”96 Commanded to take lodging in town, Croghan was billeted with two British officers charged with his close supervision.

Monckton Hall and twenty-six other country mansions were burnt after the battle of Germantown had “alarmed Howe into building a fortified line from the Schuylkill to the Delaware.”97 The General’s anger at Croghan increased as new reports reached Philadelphia of the damage his speeches to the western Indians had done to British interests. When Howe evacuated the city in

31

June, 1778, Croghan was ordered to accompany the prisoners, but “an old friend, Major General James Robertson, interceded, and Croghan was permitted to remain in Philadelphia on parole.”98

Relief in having Pennsylvania and the Continental Congress back in charge of Philadelphia was short-lived, for both accused him of having joined the armies of the enemy. Croghan’s name was linked with Alexander McKee and Simon Girty, now renegades rallying Ohio Indians to the Union Jack and raiding the frontier. Despite his infirmities, he wanted to serve the patriot cause, writing a friend that “all the western tribes might be brought to their sences with proper manidgment.”99 On November 12, 1778, Croghan appeared at court and cleared himself of treason.

If he held any illusions that the vindication would permit him to resume “acting the part of a beloved man with the swan’s wing, white pipe, and white beads, for the general good of [my] country, and of its red neighbors,”100 General Hand shattered them by forbidding Croghan’s return to Croghan Hall. He moved to Lancaster for the winter, as his property near Pittsburgh was overrun by squatters. He had sent his clerk back earlier in the year only to have him arrested by General Hand. A rumor that Hand had executed Thomas Smallman for treason proved false, but Croghan thought it best that his cousin and business partner not write to him.

With the help of the Gratzes, he tried to pay old debts, unusual for people who fail in trade, as he wrote Barnard,101 and valuable Croghan Hall was mortgaged to John Simon. The Gratzes supplied Croghan’s needs and

32

paid some of his creditors, for which Croghan deeded them 74,000 acres of his Indian grant to sell for him. Together they again traveled to Williamsburg, where Virginia reaffirmed its denial of the Indian titles. As usual after a journey, Croghan was bedridden with gout upon returning to Lancaster. Solicitous letters from family and friends went unanswered. Wintering in a house without a chimney, he wrote to the Gratzes when he needed money.

One of the instances in which they may have failed him concerned the wages of his servant. James Forrest had never received a shilling, but when he married, his wife nagged him into demanding his back pay and Croghan wrote the Gratzes for money to be rid of the “rascal.” Whether or not he was paid, Forrest remained in Croghan’s service and moved to Philadelphia with him, first to Moyamensing Township, finally to Passyunk.

In 1780 Croghan learned that his nearly eight million acres of western lands were all in Pennsylvania, but his hopes were raised in May, 1782 when a committee of Congress found that his purchases and those of the Indiana company were legitimate. James Forrest continued to serve his cash poor master, as did Croghan’s nurse, Ann Gallagher, and his physician, Dr. Abraham Chovet, who often visited his invalid patient and friend.

Susannah Prevost was bequeathed the bulk of Croghan’s estate in his June 12th will, but he was too depressed to respond to her worried letters. When he died on August 31, 1782, his gardener brought the body to town and Croghan was buried in St. Peter’s graveyard.

The sexton misspelled his name, the newspapers

33

did not mention his death, and the marker over his remains wore away. Yet Wainwright’s poetic conclusion, that “the man’s name and fame faded away into the obscurity from which he had emerged,”102 has never been true and seems absurd coming from his biographer. Croghan’s obscurity is part of the modern American myth103 that Fintan O’Toole explores in his biography of William Johnson, with whom Croghan had so much in common.

O’Toole’s Irish perspective on what his subtitle calls “the invention of America,” recognizes that “the stories that formed the basis for American mythology can be retold from any number of perspectives, but ” . . . the most powerful retellings come from the points of view of Native Americans and of African Americans.”104 His insight that Irishmen like Johnson and Croghan were cultural mediators made sensitive by the “ambivalence of the Irish situation as colonised people who became colonisers, as ‘savages’ who came to see themselves as civilisers, and as white people who often appeared to official Anglo-American eyes as virtual blacks.”105 is convincing.

Croghan embraced and exaggerated his Irishness in response to Anglo bigotry both British and colonial, bigotry that Volwiler only credits him with experiencing for being a frontiersman. Croghan may have felt Thomas Jefferson’s ambivalence as a slave owner, but there is little evidence of it. In a letter to Joseph Simon, Croghan placed an order for a teenage slave girl: “Lett the wench be likely, but don’t let her know she is for an Indian.”106 When Peters foreclosed the Pennsborough property, only

34

“four Negro slaves”107 were included and there is little mention of him owning many of them afterward, unlike fellow Irish traders William Johnson and George Galphin. Jefferson’s imprudence in living beyond his means and running into debt far outstripped Croghan’s without similar damage to his reputation. Encouraging debt among Indian leaders to force them to sell tribal land cheaply became Jefferson’s Indian policy, a prelude to their eventual extinction, regrettable but inevitable in his view. Generally, Croghan pursued a less cynical, more humane and peaceful Indian policy, not coincidentally as: “The Iroquois influence began to wane after 1745. English and French attention turned to the Ohio Country where the Iroquois had little authority. The Ohio tribes emerged as a new power bloc.”108

Only with George Croghan as the organizer and leader of the Ohio Indians do subsequent events make sense. Historians without this assumption fall into errors, such as Fred Anderson incorrectly stating that “Croghan pretended to be the representative of Pennsylvania’s government”109 at the May, 1752 Logstown conference that gave the Ohio Company permission to build a fort at the forks of the Ohio. The negative spin Anderson gives his description of Croghan as “ubiquitous” diminishes his central role to that of a kibitzer, if not parasite.

A conservative’s interpretation of Croghan’s ubiquitousness written in the mid-1920s by biographer Albert Volwiler’s says “. . . he was always present at the places were the struggle was the most critical, rendering daring and efficient service. In times of crises men looked to him for counsel and guidance.”110 Volwiler’s

35

conservatism comes to the fore when he calls Croghan one of the first “Englishmen”to recognize the value of the upper Ohio Valley and cites two great forces he encountered, the Indian trade and “the irresistible westward movement of the Anglo-Saxon settler.”111

For Volwiler, England’s dispute with France, the political troubles between England and the colonies, and jealousies between the colonies or states were of secondary importance, but for Croghan they were hardly so. At great cost he actively engaged the French in two wars only to find them an ally at Yorktown in the forced retirement of his old age, yet another irony for Francophobes like Croghan and Washington.

Croghan’s nearly thirty years of support for Virginia’s claim to western Pennsylvania were as expensive and futile as his efforts to establish Vandalia, and again ironic. For Native Americans, Virginians were the hated “long knives,” and Croghan was an Indian as well as a Pennsylvanian whose land obsession caused him to betray his adopted people and colony.

The obscenity of Dunmore’s War against the Shawnees and threatened one against western Pennsylvanians found Croghan conflicted, distrusted, but doing what he could in the public interest. That his private interests were primarily responsible for the problem in the first place was lost on no one, including himself. His quandary gave rise to his reputation as enigmatic, manipulative, devious, and in the end cost him nearly everything.

One of Volwiler’s conclusions about Croghan is that “judged by material standards he was a failure; yet he

36

was one of the most persuasive, persistent, and influential of the great American pioneers of his period . . . .”112 Volwiler adds, “and he typified, not the abnormal, but the normal development of society,”113 a compliment with a Freudian and Marxian subtext concerning Croghan’s rationality, public service, and humanity.

Peaceful may be substituted for normal in Volwiler’s appraisal of Croghan in his Preface, although the Doctrine of Normalcy, a “line chalked by Washington and Lincoln and other eminent psychiatrists,” according to G. Nash Morton in a October, 1920 letter to the editor of The New York Times, is probably what he means:

His place in American history can be more

correctly estimated if in studying Indian affairs,

the emphasis is placed upon normal trade

conditions and land relations, rather than upon

local wars with their lurid and heroic episodes.

The latter point of view pervades too much of

American historiography.114

Croghan was deeply and heroically involved in wars during which trade conditions and land affairs were anything but normal.

Yet George Croghan does represent an alternative history regarding Indian affairs, as well as being central to what occurred. The early genocidal policies of Great Britain were continued by the United States as it expanded across North America, while British Canada grew increasingly tolerant of Native Americans as it pushed west. Volwiler wrote in the 1920s when the

37

Bureau of Indian Affairs was being subjected to searing criticism by social worker John Collins, trade and land relations in Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba and the Banana Republics of Central Republic were overseen by American Marines, while at home the normal development of society Croghan is said to typify was seen in Prohibition, an unregulated stock market, and a Red Scare.

After listing some of Croghan’s services to settlers, Volwiler says “he was not yet socialistic enough in his viewpoint to see that the state would make a better landlord than an individual or a land company.”115 If this were true, Croghan would not have worked so hard to create the colony of Vandalia.

An idealistic conservative, Volwiler’s ignorance and fear of socialism distorts his view of Croghan’s public service and crucial role in early American history as a peace-maker, opponent of bigotry and racism, and shaper of events. Although Croghan’s vision of Vandalia had more feudal elements than the radical communistic republic Christian Priber created among the Cherokees in the 1730s, there are many parallels.

Croghan may have heard of Priber, who was accused of being a French agent, captured by the British, and who soon died in jail. Vandalia, with Croghan in charge of Indian affairs, was to be modeled on William Penn’s colony, whose beginning was one of the few examples anywhere of what Volwiler calls the normal development of society.

American society did not develop peacefully and prosperously for very long in the Quaker state or ever in

38

the United States, and Croghan bears considerable responsibility. To review briefly, he used the French threat to Iroquois control of the Ohio River to purchase 200,000 acres, which led him to promote the interests of the Ohio Company and Virginia, where the sale was permitted and where Native Americans were generally hated.

Pennsylvania’s proprietor Thomas Penn wanted Croghan to build a stone fort at the Point in today’s Pittsburgh as early as 1751. Croghan’s sabotage of Penn’s fort and his indispensable aid to Virginia are two critical ways he shaped events that in the short and perhaps long run were disastrous, yet led to the prominence of George Washington, a Revolution, and independence.

The Invention of America, the subtitle of O’Toole’s William Johnson biography, involved a prodigious amount of violence and mythmaking that from early on Irish immigrants played a significant role in creating. Bigotry against the Irish did not prevent Johnson, Edward Hand and seventeen or so other Irish Revolutionary generals from succeeding in America, particularly those owning large numbers of black slaves, but it may have been the determining factor in Croghan’s failure to achieve his grand dreams.

Despite tireless energy, bold vision, and unflinching courage, Croghan failed because of “bad timing, bad luck, and careless financing”116 in Wainwright’s estimation. His biographer’s insight of “a quirk in Croghan’s mind which intruded itself, time and time again, in his dealings so that all too often he ended by cheating not only his friends but himself”117 is half the

39

story, for Croghan was frequently cheated by agents of the crown and colonies.

Revolutionary governments in Philadelphia and Virginia may have found Croghan’s Irishness combined with ambition and sway over Indians more problemantic than his poor credit rating.

His actions were frequently unscrupulous; he

indulged in the most barefaced lies; he extracted

money by dishonest methods. Sometimes such

a technique brings wealth no matter how ill

deserved the reward. But with Croghan it was

different.118

His Irishness may have been the difference. Bigotry toward the Irish is vividly expressed in Hugh Henry Brackenridge’s 1795 Modern Chivalry: Containing the Adventures of Captain John Farrago and Teague O’Regan, His Servant, written and printed in Pittsburgh, the first literary work published west of the Alleghenies.

Croghan’s presence is felt in one of Brackenridge’s subjects for satire, an Indian agent who tries to recruit Teague, the Irish Sancho Panza to Captain Farrago’s Don Quixote, as an Indian chief. An uneducated Negro’s oration before the Philosophical Society in Philadelphia comprises a later chapter, but most target the Irish for ridicule, as when a fickle crowd votes for Teague on election day.

Croghan’s personality was not as contradictory or his fate as bleak as Wainwright concludes:

40

He was a complex man, one capable of raising

money by outrageous misrepresentations, and

equally capable of outstanding generosity and

philanthropy. There was a quality in his nature

that evoked the love of friends and family and,

up to a point, the confidence and respect of all.

His ability to create, to get things done, and to

get people to work together was well

appreciated by his contemporaries. Despite the

flaws in his nature, this brave, dauntless man

deserved a better fate than to die lonely and

impoverished.119

Cash poor, certainly, and perhaps with fewer visitors then he might have wished, still the poverty of Croghan’s last days has been exaggerated, as has his lack of honor.

Until the end, “He still believed that his agents could settle his affairs and rescue him from his difficulties by clearing for him an estate conservatively estimated at Ł140,000.”120 Croghan “kept himself going by selling small pieces of ground.”120 Old friends like “John Baynton, whose ruin and heartbroken death were directly attributable to his disastrous connection with Croghan,”121 kept in touch. Baynton wrote expressing sympathy for his distressed friend, saying it was a “pity that any person possessed of a generous spirit should ever be so.”122

A generous spirit that included Native Americans put Croghan at odds with the various governments employing him, as well as frontiersmen like the Paxton Boys, among whose deeds was the slaughter in 1763 of

41

the last of the Conestoga or Susquehanna tribe, by then peaceful Christians. It was the sort of atrocity that Croghan time and again was able to smooth over with condolence presents and wise counsel. Pontiac’s Rebellion was the immediate cause of the Pennsylvania frontiersmen’s thirst for revenge, an Indian war that historians agree Croghan would have prevented had General Amherst and the British government listened to him and acted on the intelligence he gathered.

Pontiac’s Rebellion was an outgrowth of the French and Indian War that also devastated the Pennsylvania frontier and enraged its people, a conflict that would have unfolded differently had Croghan built Governor Penn’s fort at the forks of the Ohio in 1751 or 1752, instead of scuttling that plan and aiding Virginia. How the Seven Years’ War might have been altered is speculation, a next to useless exercise when extended beyond the short term, yet essential in understanding and evaluating events.

George Washington’s appearance in history at this time continues to distort America’s story about itself. Once largely a vehicle to glorify Washington and later the South, promote mythology about the frontier and its heroes, and justify wars of aggression, American history remains a competition for dominance in Colin Calloway’s view:

When different historical experiences result

from shared events, history becomes a contested

ground where alternative versions of the past vie

for supremacy, and where some people’s voices

42

struggle just to be heard. As they did on the

Ohio River in the late eighteenth century,

battle lines harden because the contest is not

just about history, as it was then not just about

the land. It is also about whose vision of America

should prevail.124

Many American historians continue sacrificing a factual, inclusive, and coherent national story to ideological considerations, yet there is a counter effort to tell the neglected stories, none more important than Croghan’s.

His betrayal of Pennsylvania and Native Americans who saw in him an adopted brother, counselor, and patron had enormous consequences, including ushering George Washington onto the world stage. Washington’s cover-up of his Jumonville Glen war crime produced the Cherry Tree myth, a vigorous defense by Francis Parkman, and an ironic Parkman prize for Fred Anderson’s partial exposé, yet our narrative for the mid-eighteenth century remains confused and superficial, as does our national identity, which was forming then.

On this score much is made of Croghan’s Irishness and rightly so, for he exaggerated it mightily, yet when in London in 1764 and planning a trip to Dublin as heir to his grandfather’s estate, he had become too much of an ambitious American to take the time to visit Ireland. That other Irish-Americans had strikingly similar careers, William Johnson among the Iroquois, James Adair and George Galphin with the southern tribes, and countless less accomplished Irish traders suggests ethnic affinity for the work and a more deterministic view of past events.

43

Of the four, only Croghan did not realize his ambitions, partly because they were so gargantuan and perhaps threatening to the colonial and British Anglos wielding power. Consider again the fate of the Swiss-born Colonel Bouquet, intimately associated with Croghan as a competitor for influence on the frontier. Lionized in America and England for his military successes, he was made the first foreign British general and sent to a Pensacola, Florida pest hole where he died of fever, thereby missing by a decade the Revolution that he might have crushed in its infancy.

Similarly, the death by torture of Washington’s western Pennsylvania agent, William Crawford, a few months before Croghan died in 1782 might have been prevented had he remained on the frontier to negotiate with the Ohio Indians. Letters between Crawford and Washington in the winter of 1773-1774 concerning the disputed ownership of land in the Chartiers Creek watershed, with one of the buyers of Croghan’s property building his cabin so close to that of a Washington buyer that he could not get in the door, have a revealing coda.

Washington returned to the Pennsylvania county that bore his name to take legal action in September, 1784, two years after Crawford and Croghan had died.125 Reminding readers that dead men tell no tales as she analyzes the case, Margaret Bothwell says:

“Now here we have the strange situation of

Crawford, in December 1773, referring to the

lands as Washington’s, yet Washington’s claim,

when asserted in court eleven years later,

44

apparently hinged on an alleged patent from Lord

Dunmore dated July 5, 1775.126

On that day Washington had just taken command of the Continental Army besieging the British in Boston while Dunmore, driven from power in Williamsburg, was aboard one of their war ships on the York River.

Although Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court supposedly ruled on the ejection suit two years later, Miss Bothwell’s search for the results were unsuccessful and “the papers either misplaced or they have vanished.”127 It is irresistible to project the note of paranoia ten years forward when counselor for the buyers of Croghan’s land, Hugh H. Brackenridge, would become one of the political targets of Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s cat’s-paw during the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion.

Western Pennsylvania’s early history and indeed the nation’s origin cannot be understood outside its “Tale of Two Georges,” the rivalry for influence on the frontier between Washington and Croghan. Informed local opinion has changed little since the former’s visit in 1784: “There was no ovation in Washington County at his coming and no tears shed at his going.”128 Unfortunately few western Pennsylvanians are informed about their early history. Myths continue to obscure Washington and interest in George Croghan’s astonishing story is feeble.

Ordinary peoples’ role in history is now a major focus and Croghan was not ordinary. Women, Native and African Americans, other ethnic groups, the poor and marginalized are receiving long overdue attention from historians, but so should Crogan, the neglected Irish-born

45

King of the traders, Iroquois sachem, Indian agent, land speculator, Virginia partisan, Ohio Company officer, rival of George Washington, British official, colony projector, judge, and president of Pittsburgh’s Committee of Safety until falsely accused of being a loyalist.

Earlier historians treated Croghan with more respect and justice than today’s do, were less blind to his public service and contributions if no less oblivious to the consequences of banishing him from the frontier during the Revolution. In a recent article critical of Croghan’s self-interest, William J. Campbell wonders why would “. . . important people repeatedly entrust important missions to a known scoundrel?”129 His answer, that there was no better alternative, is as unsatisfactory as his approach.

If Campbell is typical, contemporary historians are beginning to realize Croghan’s importance in early Ohio Country history: “By detailing the complicated web of self-interest, it is clear that Croghan defined the direction of significant colonial events during the two decades that preceded the American Revolution.”130 Campbell’s conclusion quotes William M. Darlington’s 1893 assertion that Croghan was the key frontier figure “for twenty five years preceding the Revolutionary War,”131 but perpetuates the myths about Croghan that make understanding him and his times a challenge.

Darlington’s twenty-five years during which Croghan was the key Ohio Country figure becomes thirty with his lighting of the Mingo council fire at Logstown in 1747, after becoming an Iroquois sachem in 1746 and organizing the Ohio tribes first in British, then American interest until banished from the frontier in 1777.

46

NOTES

- Nicholas B. Wainwright, “An Indian Trade Failure: The Story of the Hockley, Trent and Croghan Company 1748-1752,” Pennsylvania Magazine, 72, 1948, p. 343.

- Cadwalader Collection, 1659-1933, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, Box 1, file 21, (hereafter cited as Cadwalader).

- Albert T. Volwiler, George Croghan and the Western Movement,1741-1782, Lewisburg, PA: Wennawoods Pub., 2000, p. 25, (hereafter cited as Volwiler).

- Charles A. Hanna, “George Croghan: The King of the Traders,” The Wilderness Trail: Or, the Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Vol. Two, originally published 1911, Lewisburg, PA: Wennawoods Pub., 1995, p. 84, (hereafter cited as Hanna).

- Harold Frederic and William C. Frederick III, The Westsylvania Pioneers 1746-1776, Butler, PA: Mecklin Bookbindery, 2001, p. 70, (hereafter cited as Frederic).

- Lynn Scholl Renau, So Close from Home: The Legacy of Brownsboro Road, Louisville, KY: Herr House Press, 2007, p. 16.

- Nicholas B. Wainwright, George Croghan: Wilderness Diplomat, Chapel Hill, NC: U. of North Carolina, 1959, p. 260, (hereafter cited as Wainwright). William lodged in the Indian Queen Tavern.

- Cadwalader, Box 5, file 37.

- Sir Arthur Vicars, ed, Index to the Prerogative Wills of Ireland, 1536-1810, Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co. Inc, 1997, originally published 1817, p. 112. Six

47

Croghans listed: 1767, Alice, Leitrim, co. Roscommon; 1777, Dennis Roscommon, co. Roscommon; 1801, Elizabeth, Galway Town, widow; 1779, Owen, Grange, co. Roscommon; 1768, William, Drimkeelvy, co. Leitrim, gentleman; and 1782, William, Grange, co. Roscommon.

- Hanna, p. 30.

- Fintan O’Toole, White Savage, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998, p. 57, (hereafter cited as O’Toole).

- Wainwright, p. 15.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 29.

- Ibid.

- Richard Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier 1701-1754, Lincoln, Nebraska: U. of Nebraska Press, 1997, p. 194, (hereafter cited as Aquila).

- Ibid., p. 195. Aquila unconvincingly credits the Oneida chief living at Ohio, Scarouady (p. 196), not Croghan, for organizing the new power base there.

- Ibid., p. 201.

- Wainwright, p. 28.

- Ibid.

- John Lewis Peyton, Peyton’s History of Augusta County, Virginia, Staunton, VA: Samuel M. Yost & Son, 1882, p. 75, (hereafter cited as Peyton).

- Ibid., p. 74. Peyton’s book is on the internet.

- Fred Anderson, The Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Face of Empire in British America, 1754-1766, New York: Knopf, 2000, p. 30, (hereafter cited as Anderson).

48

- Wainwright, p. 277, with oblique reference on p. 257.

- Ibid., p. 30.

- Ibid., p. 37.

- Ibid., p. 44.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- Ibid., p. 41.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 44.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 46.

- Volwiler, p. 78.

- Anderson, pp. 28-29.

- Peyton, p. 107.

- Wainwright, p. 49.

- Ibid., p. 50.

- Ibid.

- Anderson, p. 25.

- Wainwright, p. 58.

- Jim Greenwood, Jumonville Glen, May 28, 1754; Day of Infamy, Belle Vernon, PA: Monongahela Press, 2002, pp. 21-22.

- Ibid., p. 1.

- Wainwright, p. 65.

- Ibid., p. 169.

- Ibid., p. 207.

- Ibid., p. 206.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 207.

49

- Ibid., p. 230.

- Ibid., p. 212.

- Ibid., p. 220.

- Ibid., p. 221.

- Ibid., p. 225.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 231.

- Ibid., p. 232.

- Ibid., p. 244.

- Ibid., p. 58.

- Ibid.

- Wainwright, p. 176.

- Cadwalader, Box 7, file 53.

- Wainwright, p. 243.

- Ibid., p. 248.

- Ibid., p. 252.

- Cadwalader, Box 8, file 14.

- Wainwright, p. 257.

- Ibid., p. 266.

- Ibid., p. 269.

- Ibid., p. 270.

- Ibid., p. 271.

- Ibid., p. 273.

- Ibid., p. 274.

- Frederic, p. 75.

- Ibid.

- Peyton, p. 75.

- Wainwright, p. 279.

- Ibid., p. 245.

- Ibid., p. 282.

50

- Ibid., p. 283.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 286.

- Volwiler, p. 25.

- Ibid., p. 288.

- Ibid., p. 292.

- Ibid., p. 295.

- Ibid., p. 297.

- Ibid., p. 299.

- Ibid., p. 301.

- Ibid., p. 327.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 302.

- Ibid., p. 303.

- Ibid., p. 238.

- Ibid., p. 310.

- O’Toole, p. ix.

- Ibid., p. x

- Ibid.

- Jacob R. Marcus, “How Jews Treated Their Slaves,” The Colonial American Jew, 1492-1776: Vol. II of III. Detroit, MI: Wayne State U. Press, 1970, p. 705.

- Wainwright, p. 44.

- Aquila, p. 245.

- Anderson, p. 26.

- Volwiler, p. 112.

- Ibid., p. 334.

- Ibid.

51

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 335.

- Wainwright, p. 308.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 309.

- Ibid., p. 306.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 309.

- Ibid., p. 310.

- Colin G. Calloway, The Shawnees and the War for America, New York: The Penguin Library of American Indian History, 2007, pp. 174-75.

- Margaret Pearson Bothwell, “The Astonishing Croghans,” Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, April, 1965, 48:2, p. 139.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 140.

- William C. Campbell, “An Adverse Patron: Land, Trade, and George Croghan,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, 2009, 76:2, p. 118.

- Ibid., p. 119.

- Ibid., p. 134.

52

Works Cited

Anderson, Fred. The Crucible of War. New York: Knopf, 2000.

Aquila, Richard. The Iroquois Restoration. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P., 1997.

Bothwell, Margaret Pearson. “The Astonishing Croghans.” Western Pennsylvania

History Magazine 48(2) April, 1965: 119-144.

Cadwalader Collection, 1659-1933. Historical Society of Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia, PA.

Campbell, William C. “An Adverse Patron: Land, Trade, and George Croghan.

“Pennsylvania History 76(2) 2009: 117-140.

Calloway, Colin G. The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Penguin, 2007.

Frederic, Harold, and William C. Frederick III. The Westsylvania Pioneers 1746-1776.

Butler, PA: Mecklin, 2001.